Post by MinnesotaNationalist on Aug 31, 2016 21:10:38 GMT

What is Europe but You and We?

The Empires of East and West will drive the Turks from Europe, then march on to Conquer India

Divide the Empire of the World

A scenario where Napoleon and Alexander's Alliance of 1807 doesn't break down as early:

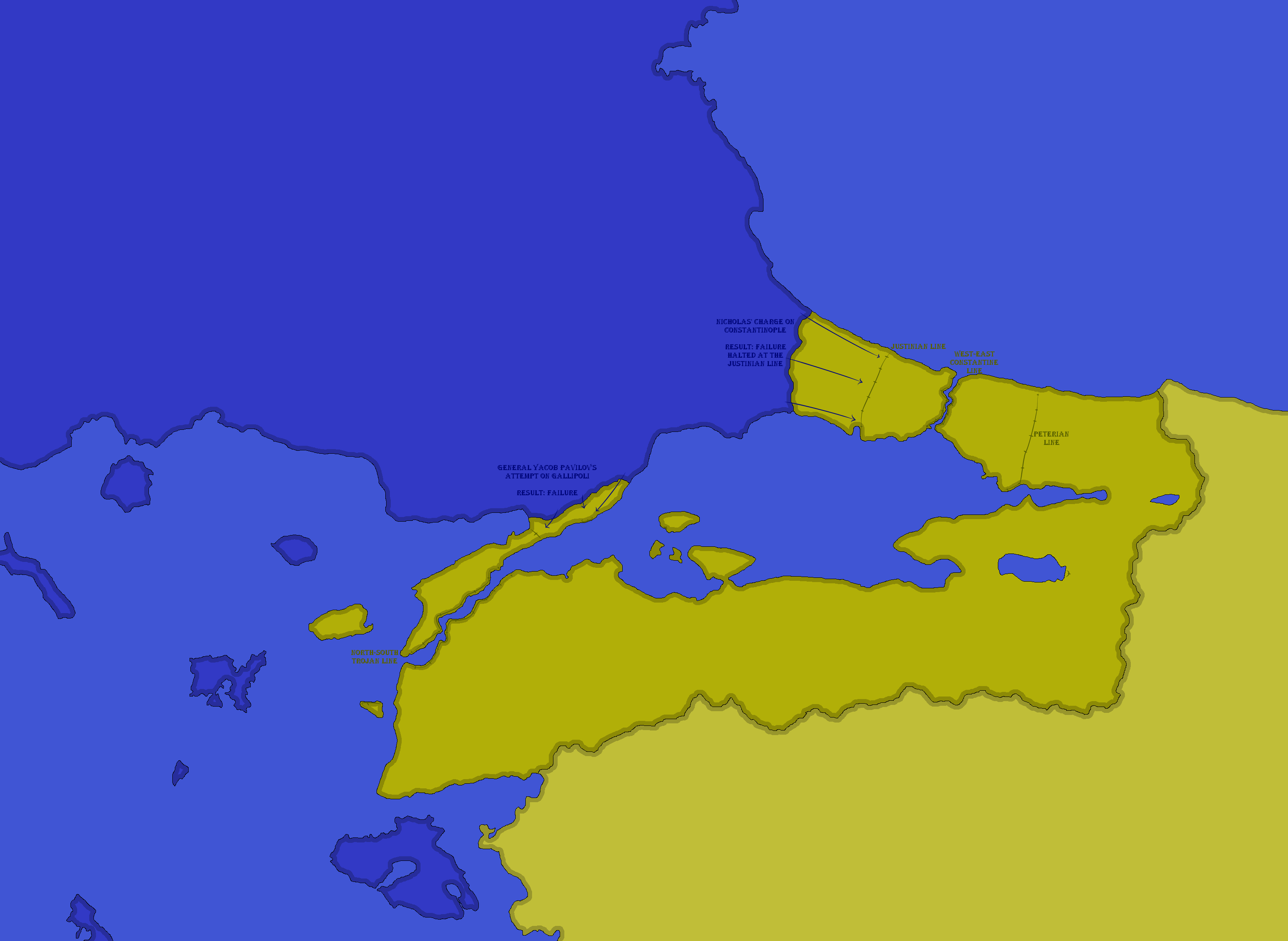

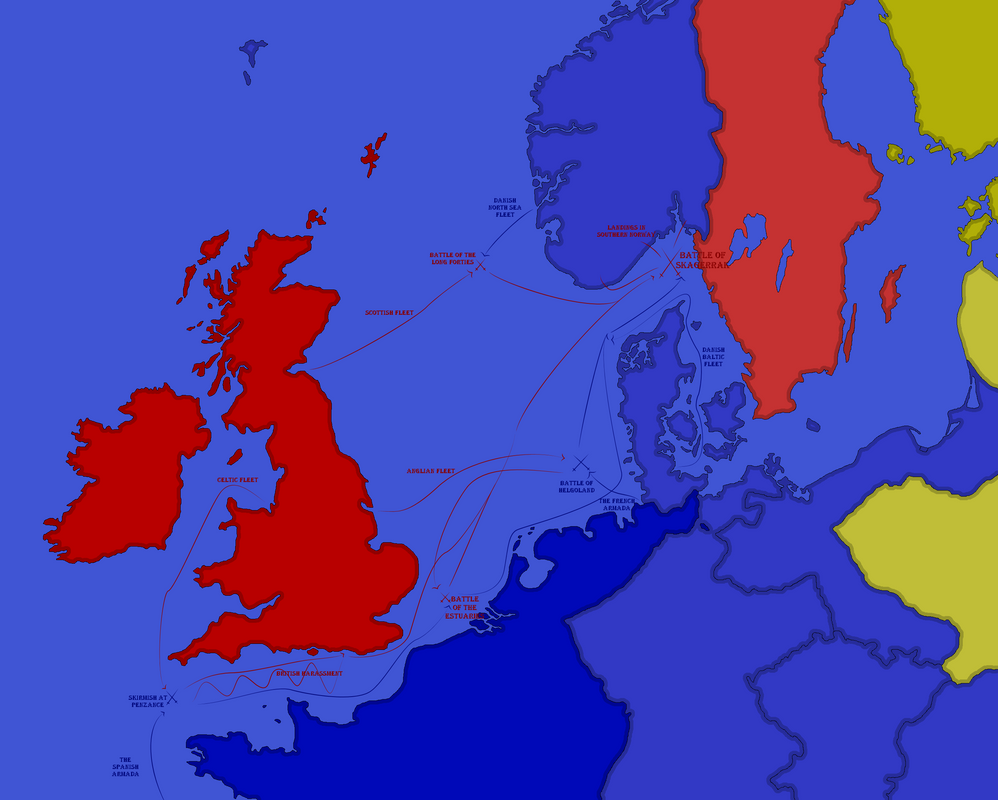

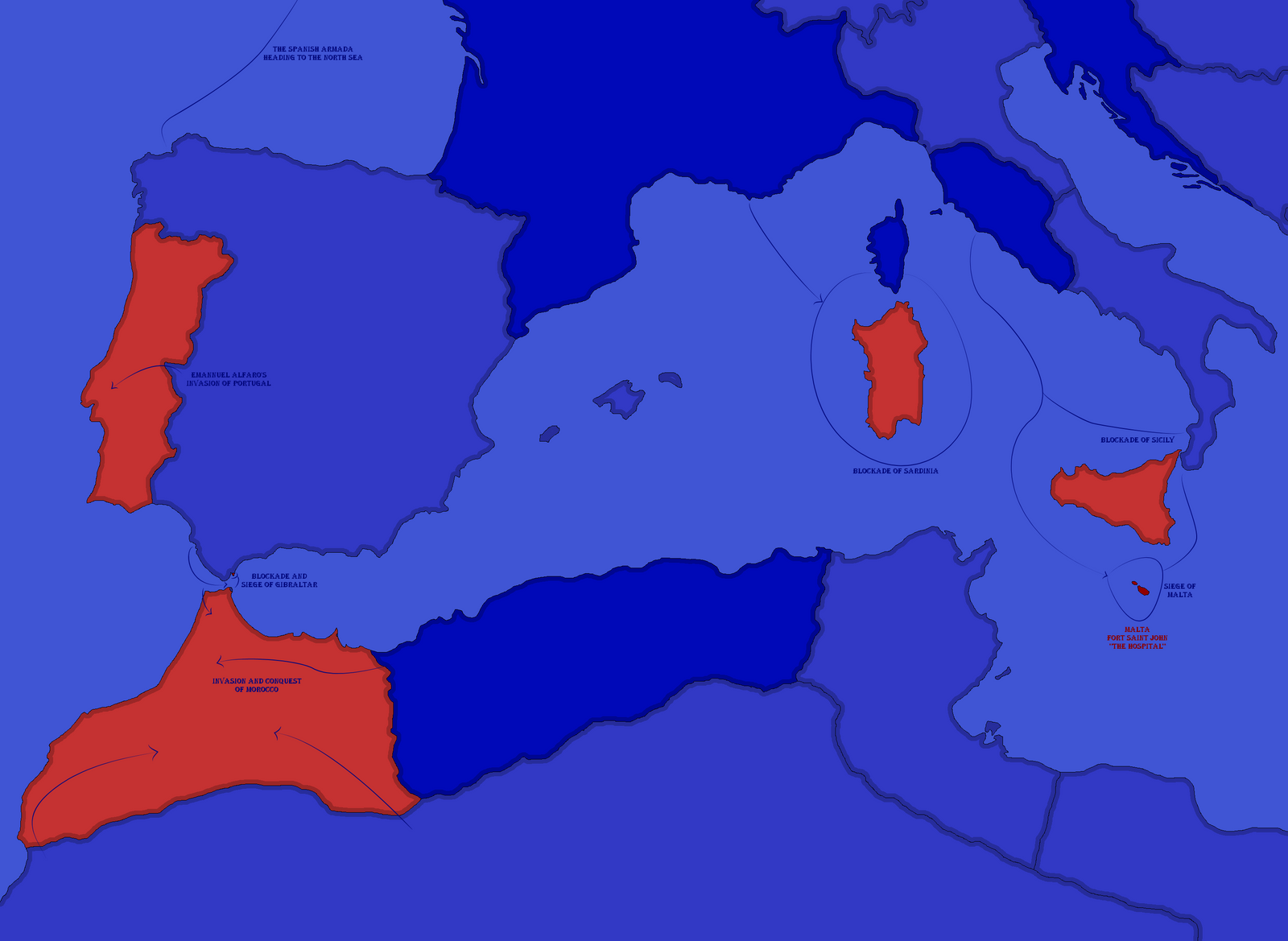

In November of 1807, Napoleon launches a campaign against the Ottomans, aiding his ally of Russia, but the Ottomans proved a tougher fight than suspected, and it didn't help that Alexander and Napoleon were constantly bickering (mostly Napoleon's fault), leading to Napoleon to withdraw from the Ottoman Campaign numerous times for a couple of months, before the Ottomans finally surrendered in 1814.

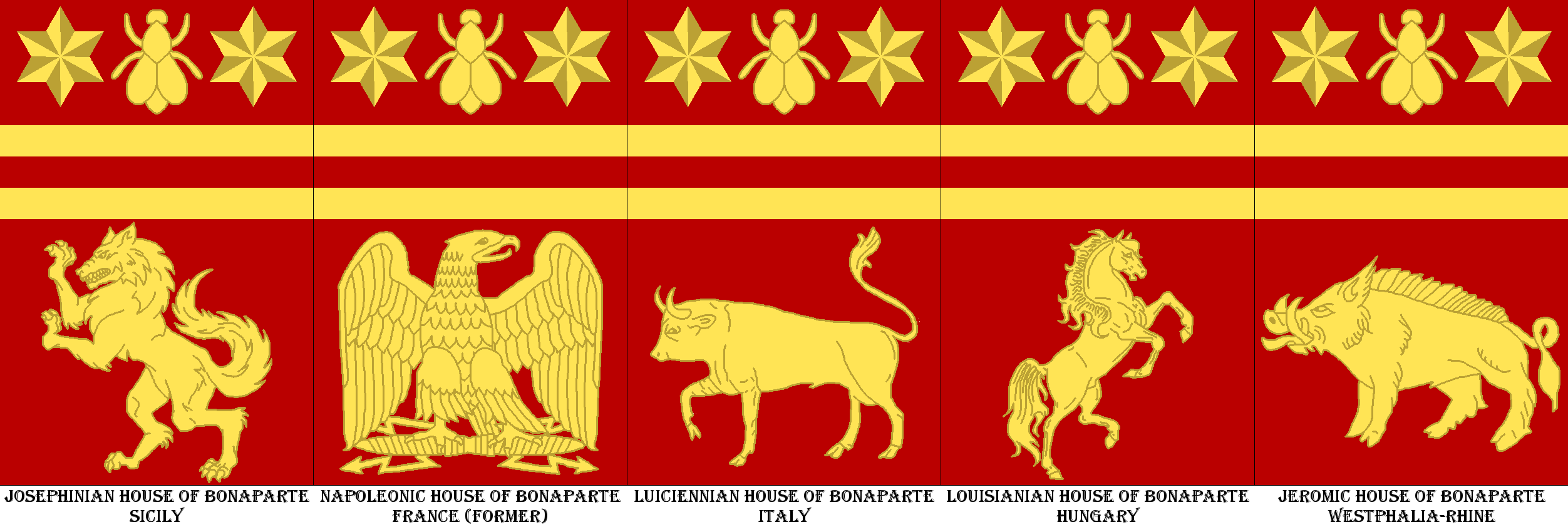

Alexander and Napoleon met at Sofia to finally try to settle their differences, leading to the "1,000 Agreements of Sofia," where Napoleon and Alexander continuously gave concessions to each other, dividing the influence of Europe. In general, Napoleon wanted influence over the Catholics and Romance people, while Alexander wanted sway over the Orthodox and Slavic people. Well, they'd be butting heads over the Catholic Slavs and the Romanians. While Napoleon did cede concession over Romania, Alexander and Napoleon did debate harshly over Poland and Yugoslavs. They finally came to the conclusion of shared influence over the two states of Poland and Serbia.

Among other things, Greece was declared shared influence in return for Russia getting Constantinople, Russia getting Antioch and Jerusalem (under puppets) for shared influence over Albania, a 'press here to divide button' for Sweden between both France and Russia, and according to legend, Alexander would accept all French annexations up to this point if Napoleon would cut off one of his generals fingers.

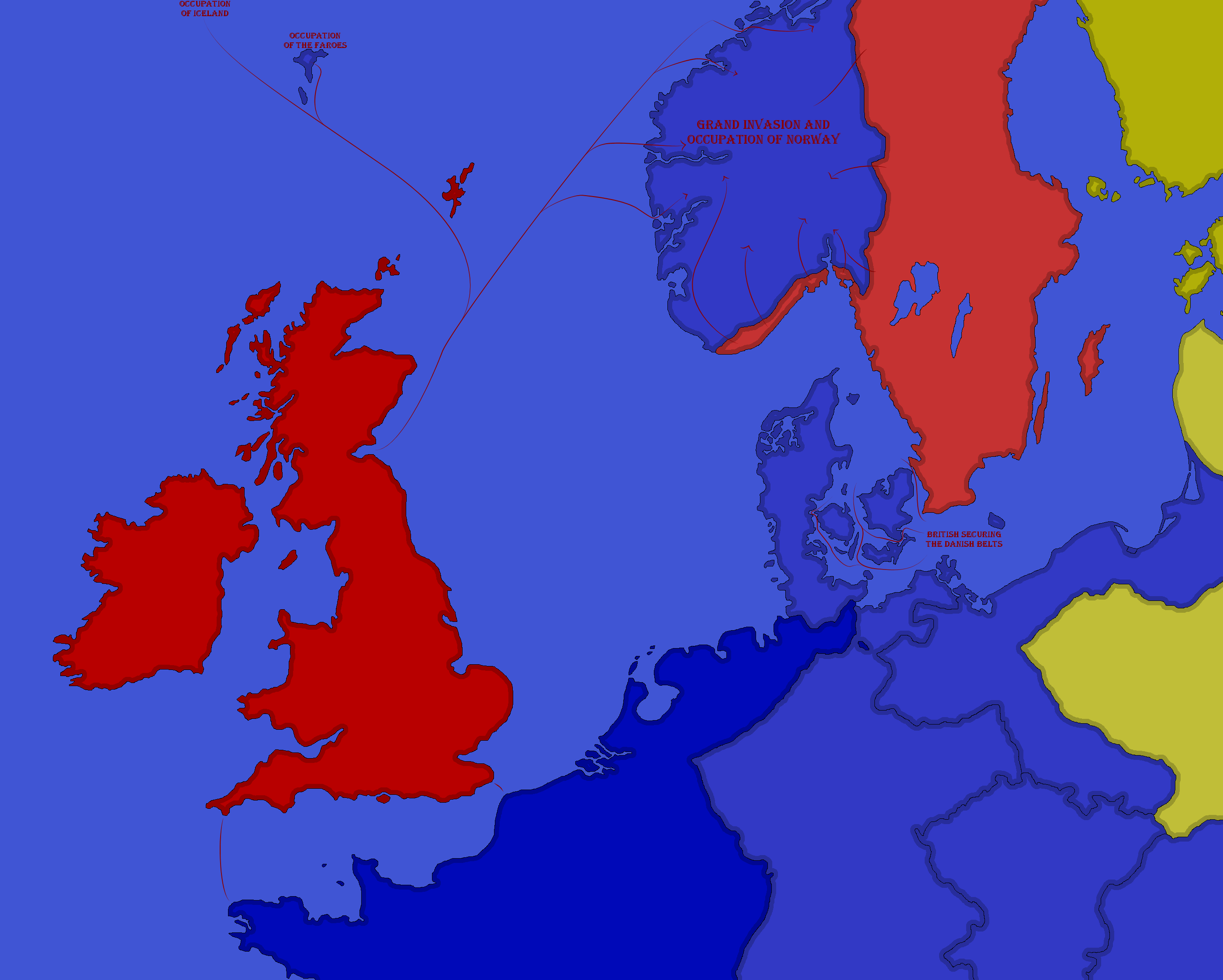

With the vast majority of Europe now divided between Napoleon and his allies, Napoleon's ambition seems to be over, if it weren't for that Alexander's and Napoleon's relations started to deteriorate once more, leading to the breaking of the alliance in 1816, although Alexander's embargo of the UK continued (to explain in Alexander's own words, "I hate England, too."), and so the world has divided the world into 3 major spheres: The French Sphere, the Russian Sphere, and the British Sphere (There's also the Post-Turkish Sphere, but their interest tend to remain aligned with the British Sphere).

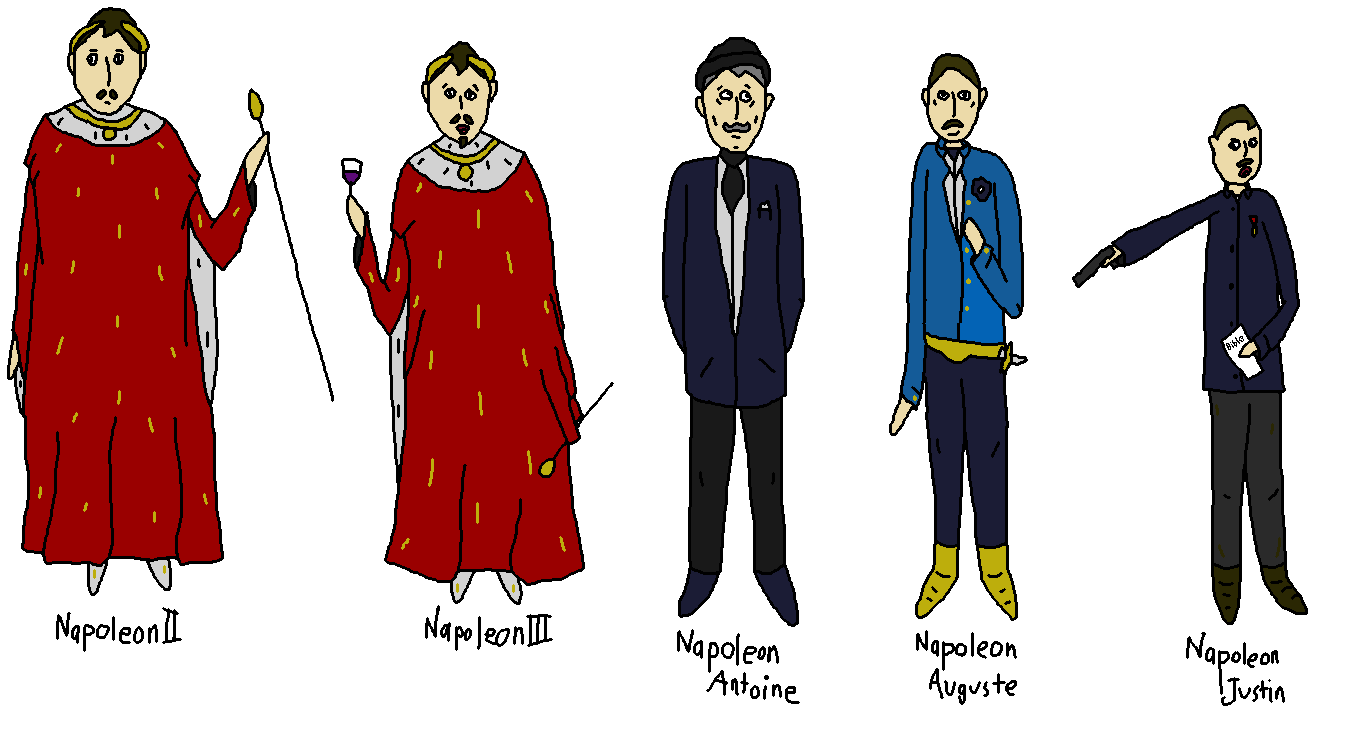

Alexander of Russia died in 1825, leaving the nation and it's sphere to his younger brother. Napoleon himself died in 1831, leading to the rise of Napoleon II. He was certainly not his father, but was still a good enough ruler to take on the Reigns of Europe

Alexander and Napoleon met at Sofia to finally try to settle their differences, leading to the "1,000 Agreements of Sofia," where Napoleon and Alexander continuously gave concessions to each other, dividing the influence of Europe. In general, Napoleon wanted influence over the Catholics and Romance people, while Alexander wanted sway over the Orthodox and Slavic people. Well, they'd be butting heads over the Catholic Slavs and the Romanians. While Napoleon did cede concession over Romania, Alexander and Napoleon did debate harshly over Poland and Yugoslavs. They finally came to the conclusion of shared influence over the two states of Poland and Serbia.

Among other things, Greece was declared shared influence in return for Russia getting Constantinople, Russia getting Antioch and Jerusalem (under puppets) for shared influence over Albania, a 'press here to divide button' for Sweden between both France and Russia, and according to legend, Alexander would accept all French annexations up to this point if Napoleon would cut off one of his generals fingers.

With the vast majority of Europe now divided between Napoleon and his allies, Napoleon's ambition seems to be over, if it weren't for that Alexander's and Napoleon's relations started to deteriorate once more, leading to the breaking of the alliance in 1816, although Alexander's embargo of the UK continued (to explain in Alexander's own words, "I hate England, too."), and so the world has divided the world into 3 major spheres: The French Sphere, the Russian Sphere, and the British Sphere (There's also the Post-Turkish Sphere, but their interest tend to remain aligned with the British Sphere).

Alexander of Russia died in 1825, leaving the nation and it's sphere to his younger brother. Napoleon himself died in 1831, leading to the rise of Napoleon II. He was certainly not his father, but was still a good enough ruler to take on the Reigns of Europe

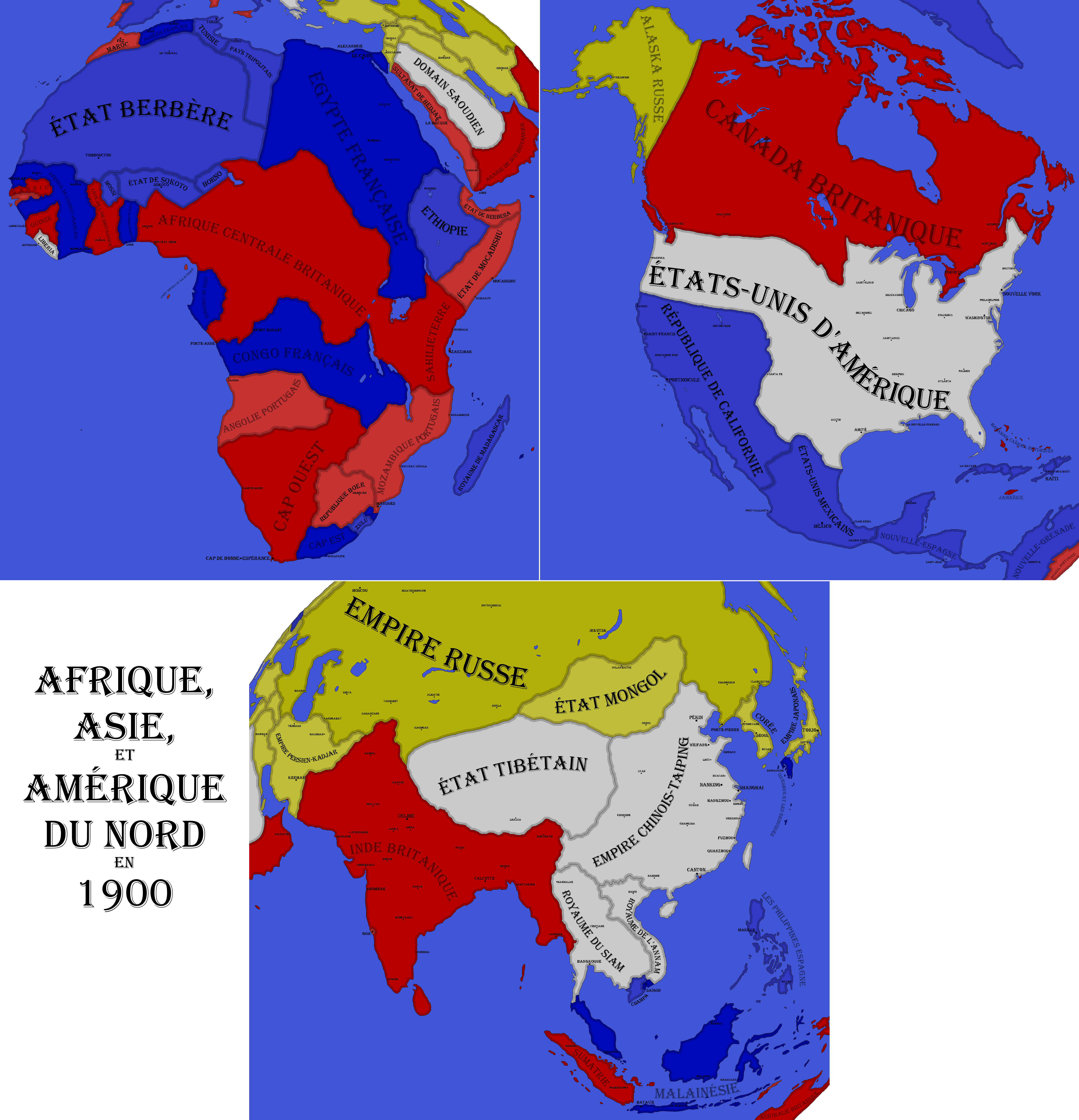

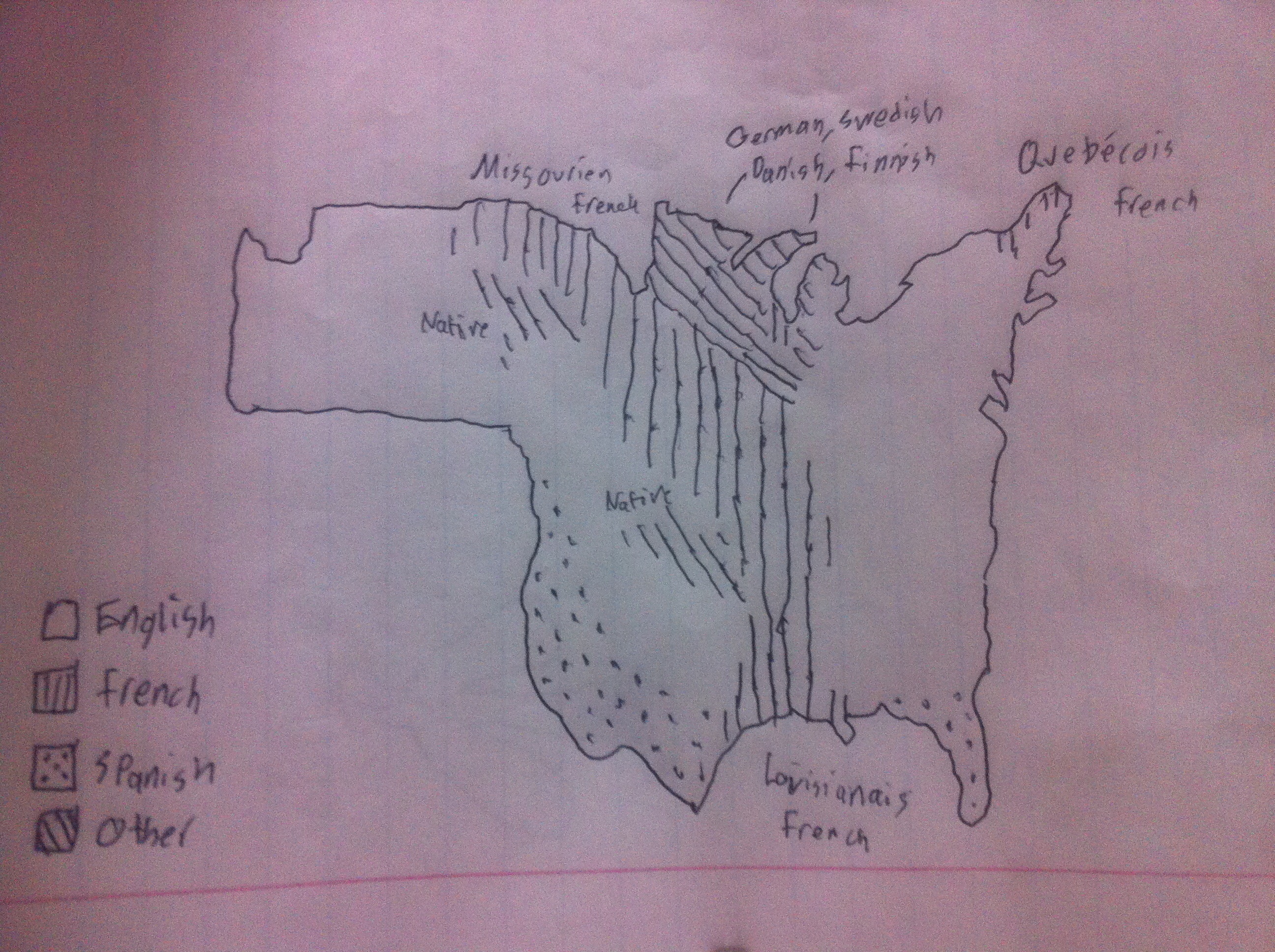

North America

Following the victory of Napoleon and Franco-Russian alliance over the Ottomans at the treaty of Sofia, Britain came to realize their chances at victory was close to none. They declared their intention of peace and in the early months of 1815, all the leaders of Europe of met at Amsterdam and fell to three factions, one led by Napoleon and France, one by Alexander and Russia, and one by Spencer Perceval of Britain in the name of George III.

The conditions of the Peace were thus:

Peace remains in Europe after the Treaty of Amsterdam, however tenuous, and Britain has more-or-less conceded the continent to France and Russia. In the Americas, Africa, and Asia however, the three remain in Competition, with Britain and France being the main competitors in America.

The Three minor Republics who gained their independence at Amsterdam; Mexico, Haiti, and California, who were originally intended to be British allies, have ended up in the French Sphere nonetheless.

The Grand prize however is the United States, who, while officially neutral, certainly does have many French leanings, mostly due to lingering British resentment, although there is certainly a possibility of the US leaning back to Britain.

Since the Treaty of Amsterdam, the US and Britain remains in conflict over the US-Canadian border. They hope the most recent treaty of Toronto (1846) will end the conflict, but the US will undoubtedly want to expand her western coast.

The United States have also had some conflict with France (or more specifically, Spain) over Florida. This conflict was able to be resolved diplomatically though, with the US gaining Florida from Spain, Texas from Mexico, and France would aid the US in it’s endeavour to gain a coast on the Pacific (Oregon), but US must make no demands on any other Franco-Sphere state.

British and Anglo-Sphere colonies in the Americas are minimal poor, compared to the vast tracts of land in the Franco-sphere, but if the US realigns to Britain, she could still win on the American Front.

Asia

Since the Treaty of Amsterdam, Britain is looking everywhere for new ports, especially since the Continental Embargo in Europe remains in effect. The land most full of potential: Asia. Britain has had a monopoly on most of India since the 7 years’ war, but China offers even more goods. But, China had longed only for money for their own goods, but had no lust for anything else… Legal anyways.

In 1824, Britain opened the Chinese wars with the First Sino-British war. By 1830, victory had been achieved and Britain gained Hong Kong and forced open many Chinese ports to free trade, in British favor of course.

Nicholas of Russia, seeing how weak China really was, went to war with China next in 1832, with the war ending in 1835. Russia ripped China to pieces, forcing the independence of Tibet and Mongolia (the latter as a direct puppet of Russia), annexed large portions of North-west and North-East China, and made Manchuria and Korea as part of its sphere of influence.

In 1839, France also got in on the Chinese trade, but rather than warring with China, they rather just bought off a piece of land to influence, mostly just to piss off Russia and Britain. Strangely, all Chinese wares seem to be directed to that area for some reason…

Russia and Britain, as OTL, are squaring off over influence over Central Asia and Persia. Russia seems to have the upper hand in this Great Game.

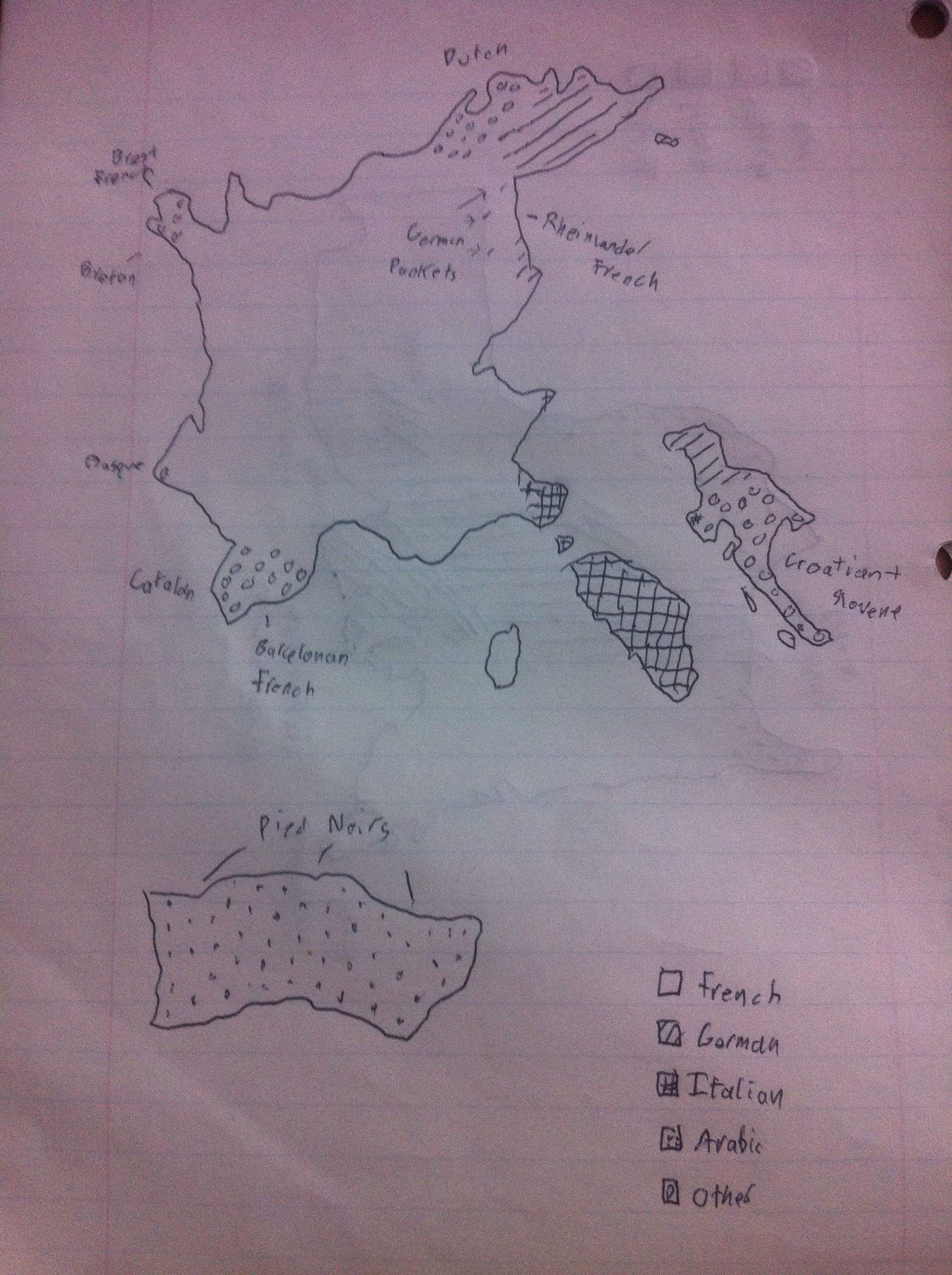

Africa

“Africa: A land created by God for the explicit purpose so that England and France may continue to fight.” -Prime Minister Charles Grey of Britain

While Britain has given up on Europe and is fighting diplomatic battles in the Americas and Asia, Africa is charged with conflict. Between the Treaty of Amsterdam and today (1850), there have been at least 7 recorded incidents, crises, and minor conflicts between France and England in Africa, most notably of which is the Boer Conflict, in which Napoleon II ordered a failed invasion of the Boer Republic, an ally of Britain, in 1843.

While there’s been fairly little expansion in the region since Amsterdam, that isn’t to say there hasn’t been any. In 1825, Napoleon I invaded and conquered the Berber state of Algeria and turned Tunis into a puppet. There has also been expansion of the spheres of influence over the native tribes and Kingdoms. For example, France has been able to get Dahomey, the Zulu, and many Berbers to align with them, while Britain’s gotten Togo, Benin, the Sultanate of Zanzibar and of course the Boers to align with herself, not to mention Portugal’s own satellite of the Kongo Kingdom.

On the Diplomatic front, there’s two current grand prizes for France and Britain: Egypt, part of the Post-Turkish Sphere and as such has much more British-leaning tendencies, whom have a very intriguing position having coasts on two oceans; and the Caliphate of Sokoto, who runs their own minor faction of the Fulani Jihadist States, and they are all very cautious of the Christian Europeans, but there surely must be riches in West Africa, such as the famous gold mines of Mansa Musa.

Following the victory of Napoleon and Franco-Russian alliance over the Ottomans at the treaty of Sofia, Britain came to realize their chances at victory was close to none. They declared their intention of peace and in the early months of 1815, all the leaders of Europe of met at Amsterdam and fell to three factions, one led by Napoleon and France, one by Alexander and Russia, and one by Spencer Perceval of Britain in the name of George III.

The conditions of the Peace were thus:

- Britain would recognize the Treaty of Sofia.

- Britain would make peace with the United States (retain the status quo).

- Britain would respect all French Annexations in Europe and elsewhere up to this point.

- Britain would cede: Heligoland, Channel Islands, and British Guyana to France, surrender all claims on the Kingdom of France and the Electorate of Hannover, and cede Belize to the Spanish Vice royalty of New Spain

- Sweden would cede Swedish Pomerania to the Confederation of the Rhine and surrender her claims on Finland.

- France would cede: Cape Town (West Cape Colony), Sumatra, and West Timor to Britain from former Dutch Territories.

- France and the rest of Europe would recognize the independence of Haiti, Mexico, and California from former French and Spanish Colonies.

Peace remains in Europe after the Treaty of Amsterdam, however tenuous, and Britain has more-or-less conceded the continent to France and Russia. In the Americas, Africa, and Asia however, the three remain in Competition, with Britain and France being the main competitors in America.

The Three minor Republics who gained their independence at Amsterdam; Mexico, Haiti, and California, who were originally intended to be British allies, have ended up in the French Sphere nonetheless.

The Grand prize however is the United States, who, while officially neutral, certainly does have many French leanings, mostly due to lingering British resentment, although there is certainly a possibility of the US leaning back to Britain.

Since the Treaty of Amsterdam, the US and Britain remains in conflict over the US-Canadian border. They hope the most recent treaty of Toronto (1846) will end the conflict, but the US will undoubtedly want to expand her western coast.

The United States have also had some conflict with France (or more specifically, Spain) over Florida. This conflict was able to be resolved diplomatically though, with the US gaining Florida from Spain, Texas from Mexico, and France would aid the US in it’s endeavour to gain a coast on the Pacific (Oregon), but US must make no demands on any other Franco-Sphere state.

British and Anglo-Sphere colonies in the Americas are minimal poor, compared to the vast tracts of land in the Franco-sphere, but if the US realigns to Britain, she could still win on the American Front.

Asia

Since the Treaty of Amsterdam, Britain is looking everywhere for new ports, especially since the Continental Embargo in Europe remains in effect. The land most full of potential: Asia. Britain has had a monopoly on most of India since the 7 years’ war, but China offers even more goods. But, China had longed only for money for their own goods, but had no lust for anything else… Legal anyways.

In 1824, Britain opened the Chinese wars with the First Sino-British war. By 1830, victory had been achieved and Britain gained Hong Kong and forced open many Chinese ports to free trade, in British favor of course.

Nicholas of Russia, seeing how weak China really was, went to war with China next in 1832, with the war ending in 1835. Russia ripped China to pieces, forcing the independence of Tibet and Mongolia (the latter as a direct puppet of Russia), annexed large portions of North-west and North-East China, and made Manchuria and Korea as part of its sphere of influence.

In 1839, France also got in on the Chinese trade, but rather than warring with China, they rather just bought off a piece of land to influence, mostly just to piss off Russia and Britain. Strangely, all Chinese wares seem to be directed to that area for some reason…

Russia and Britain, as OTL, are squaring off over influence over Central Asia and Persia. Russia seems to have the upper hand in this Great Game.

Africa

“Africa: A land created by God for the explicit purpose so that England and France may continue to fight.” -Prime Minister Charles Grey of Britain

While Britain has given up on Europe and is fighting diplomatic battles in the Americas and Asia, Africa is charged with conflict. Between the Treaty of Amsterdam and today (1850), there have been at least 7 recorded incidents, crises, and minor conflicts between France and England in Africa, most notably of which is the Boer Conflict, in which Napoleon II ordered a failed invasion of the Boer Republic, an ally of Britain, in 1843.

While there’s been fairly little expansion in the region since Amsterdam, that isn’t to say there hasn’t been any. In 1825, Napoleon I invaded and conquered the Berber state of Algeria and turned Tunis into a puppet. There has also been expansion of the spheres of influence over the native tribes and Kingdoms. For example, France has been able to get Dahomey, the Zulu, and many Berbers to align with them, while Britain’s gotten Togo, Benin, the Sultanate of Zanzibar and of course the Boers to align with herself, not to mention Portugal’s own satellite of the Kongo Kingdom.

On the Diplomatic front, there’s two current grand prizes for France and Britain: Egypt, part of the Post-Turkish Sphere and as such has much more British-leaning tendencies, whom have a very intriguing position having coasts on two oceans; and the Caliphate of Sokoto, who runs their own minor faction of the Fulani Jihadist States, and they are all very cautious of the Christian Europeans, but there surely must be riches in West Africa, such as the famous gold mines of Mansa Musa.

The Great Gamble- Taiping Revolution 1851-1858

Ever since the First Sino-British War and the Sino-Russian War, the Qing Dynasty of China had been French leaning in alignment. Russia and Britain didn’t like this, as this was one state that was too valuable to be allowed in French hands. But, Russia and Britain couldn’t find a way to break this and move the Qing to their sphere of influence.

At least, that was until the Taipings rose up in early 1851 to remove the Qing dynasty. Suddenly, the European Powers had a chance to make a great shift in the influence over China. If said European powers helped the Qing quash the Taipings, than the Qing would likely be grateful for the help and open up more to them, but if they failed and the Taipings were to win, they’d likely lose all influence over China. The reverse would be true as well.

France was unlikely to aid the Taipings because they were already fairly friendly with the Qing Dynasty, leaving Russia and Britain to decide if they want to gamble on the Taiping to remove French influence from China. Russia and Great Britain were already locked in a Great Game over Central Asia and Persia, but, in the Summer of 1851, they decide to put aside their problems for now and agreed to the Great Gamble: Aid the Taiping, overthrow the Qing, defeat the French in China.

French troops were already deployed in China, under orders of Napoleon II, to police the areas they influenced (he hoped that it would help improve the relations with the Qing if they less territory that their soldiers needed to patrol. Qing didn’t see it that way), but when the Taipings started their rebellion, Napoleon saw it as an opportunity to help and improve relations with the Qing, so ordered his troops to aid the Qing in putting it down. Unbeknownst to him, Britain had landed their first division of troops Canton, quickly capturing the city and setting it up as their center of command in Southern China, their main naval port and main supply port. In the north, Russia prepared for a quick surprise invasion to capture Beijing and force a quick surrender.

French and British troops first fought in September of 1851 near Changsha, on the Taipings’ attempted march on Shanghai*. French troops were able to stop their march, but the Taipings captured Changsha on the retreat. This would become the main command center of the Brits and Taipings in Central China, while Wuhan in the north would become the main command center of the Qing and French in the same region. Russia would invade in October 1851, and by the time snow came to China that year, Beijing was under siege.

*It should be noted, in the European influenced areas, most of the time the only Europeans there were merchants. Only France patrolled their area with their personal soldiers. After Britain and Russia intervened, all Europeans in their former areas of influence were executed unless they could prove to be, in fact, French or French influenced (Spanish, German, etc.)

Central theatre: British vs. French

As you can imagine, most of the war on this front was between the cities of Changsha and Wuhan. The first major full French (to be used for the Central Theatre instead of the Northern Theatre) and British reinforcement-armies arrived in spring of 1852, where they were immediately sent to fight along the Changsha-Wuhan front. The Changsha-Wuhan front went quickly into a deadlock, and would stay like this for years. In 1853, another French contingent arrived in Shanghai, and was determined to march south to capture Hong Kong and Canton and secure every port on the way.

Sadly for the French, another contingent of British arrived in Canton not long later, and was given the same orders. They met near Quanzhou. A hard battle was fought, but the Brits secured victory when another battalion moved in from the Changsha-Wuhan front and secured the victory at Quanzhou. The British army marched north before being stopped at Fuzhou not to far away.

For the next 3 years the fronts had stalled at Changsha and Fuzhou, before finally in 1856, a breakthrough happened for the British as Qing manpower was finally depleting, either running to the enemy or just simply abandoning their post. Wuhan would finally fall in August of 1856, and is seen as the end of the the Central Theatre and the traditional war.

Northern theatre: Russians vs. French

The first French reinforcement to arrive in China came in early 1852, where they went to try to relieve Beijing. In the Relief of Beijing, French troops were able to open a passage, but only long enough to save the Imperial family, after which the opening broke and Beijing would fall in March. The Royal family would be sent to Nanjing to witness their empire collapse around them.

Unlike the Central theatre, the Northern theatre was vast and mobile, stretching from the Tibetan border to the Yellow Sea. Xi’an and Weifang were both major centers of battle, each falling at least three times to the opposing side. Nanjing itself was under threat two separate times.

The war finally swept into Russian once and for all in 1856 at yet another battle of Xi’an, where Chinese manpower finally ran to low and in September 1856, a month after the fall of Wuhan, Nanjing would fall and the Qing emperor would go into exile in Paris.

The Marauders’ war: The Qing-French resistance

In August 1856, the French armies were getting onto their boats in Shanghai to leave for back home. One army group, under the leadership of General Philippe Sainte-Marie, decided to stay behind however, to fight a guerrilla war. Sainte-Marie and a thousand men, 900 of which were part of the Qing family or the most loyal Qing soldiers, snuck out of the front near Nanjing and made their first attack not to far away. Another 2 years of a lesser war had begun.

The first couple months was made up of heading north on the Yellow toward Beijing, raiding Russo-Taiping army camps and generally pro-Taiping villages. Sainte-Marie’s army always made sure to stay just out of reach of the opposing armies, and couldn’t be caught, no matter how much Russian armies chased them. Sainte-Marie’s army finally disappeared in December of 1856 in Beijing, where they stayed for the winter, blending into the city. Many of civilians in Beijing who were still loyal to the Qing decided to join the cause, and in March of the following year, Sainte-Marie’s army left Beijing, left it by burning it to the ground. With Sainte-Marie’s army grown to 10,000 and committing such a crime as burning Beijing to the ground, the Taiping, Russians, and Brits were to make sure that Sainte-Marie’s army would be stopped. Even Napoleon II, when hearing of what Sainte-Marie did, declared that he and all the Qing family that joined him were no longer welcome in France (unless they won).

After burning Beijing, Sainte-Marie’s army (commonly referred to as the Marauder’s Army, Philippe Sainte-Marie himself gaining the title as “Philippe the Marauder”) headed south to the Yellow River to go up and down that hitting Xi’an, Ordos, Wuhai, then took a shortcut back to raid Xi’an again and heading south to raid the Yangtze. The Marauder’s Army raided Chongqing, and was heading to attack Wuhan, but upon hearing that the Taiping Imperial Army was there waiting for him, the Marauder’s Army turned sharply south to Changsha (how fitting). Again, burning Changsha to the ground, the army headed further south before disappearing somewhere near Canton/Guangzhou in December. The Taiping Imperial Army searched frantically for the Marauder in Guangzhou, but he couldn’t be found anywhere. It sure didn’t help that he was actually hiding in Nanning two hundred kilometers west, but the Taipings wouldn’t figure that out until Nanning was also burned to the ground the following spring, and the Marauders went on another campaign.

Philippe Sainte-Marie thought of a clever plan that instead of heading further west to run away from the Taiping Imperial Army, he was just sneak around it by heading south, attack Zhanjiang and then go on to Guangzhou. This proved to be a mistake, for as soon as the Taiping Imperial Army heard of the attack on Zhanjiang, they would only be about a 6 hour’s travel behind them. There was no attempting to hide, for if they hid they would be found. If they stayed to for too long in a city the TIA would catch them, they could barely actually raid anymore. They had to spend an extra hour each day travelling just to get extra distance on the TIA, but in June they were finally caught in the city they started in, Shanghai. All the Marauder’s were either killed in the skirmish at Shanghai or executed not long later. Philippe the Marauder himself would get special treatment… A lifetime in the Taiping Oubliette.

Ever since the First Sino-British War and the Sino-Russian War, the Qing Dynasty of China had been French leaning in alignment. Russia and Britain didn’t like this, as this was one state that was too valuable to be allowed in French hands. But, Russia and Britain couldn’t find a way to break this and move the Qing to their sphere of influence.

At least, that was until the Taipings rose up in early 1851 to remove the Qing dynasty. Suddenly, the European Powers had a chance to make a great shift in the influence over China. If said European powers helped the Qing quash the Taipings, than the Qing would likely be grateful for the help and open up more to them, but if they failed and the Taipings were to win, they’d likely lose all influence over China. The reverse would be true as well.

France was unlikely to aid the Taipings because they were already fairly friendly with the Qing Dynasty, leaving Russia and Britain to decide if they want to gamble on the Taiping to remove French influence from China. Russia and Great Britain were already locked in a Great Game over Central Asia and Persia, but, in the Summer of 1851, they decide to put aside their problems for now and agreed to the Great Gamble: Aid the Taiping, overthrow the Qing, defeat the French in China.

French troops were already deployed in China, under orders of Napoleon II, to police the areas they influenced (he hoped that it would help improve the relations with the Qing if they less territory that their soldiers needed to patrol. Qing didn’t see it that way), but when the Taipings started their rebellion, Napoleon saw it as an opportunity to help and improve relations with the Qing, so ordered his troops to aid the Qing in putting it down. Unbeknownst to him, Britain had landed their first division of troops Canton, quickly capturing the city and setting it up as their center of command in Southern China, their main naval port and main supply port. In the north, Russia prepared for a quick surprise invasion to capture Beijing and force a quick surrender.

French and British troops first fought in September of 1851 near Changsha, on the Taipings’ attempted march on Shanghai*. French troops were able to stop their march, but the Taipings captured Changsha on the retreat. This would become the main command center of the Brits and Taipings in Central China, while Wuhan in the north would become the main command center of the Qing and French in the same region. Russia would invade in October 1851, and by the time snow came to China that year, Beijing was under siege.

*It should be noted, in the European influenced areas, most of the time the only Europeans there were merchants. Only France patrolled their area with their personal soldiers. After Britain and Russia intervened, all Europeans in their former areas of influence were executed unless they could prove to be, in fact, French or French influenced (Spanish, German, etc.)

Central theatre: British vs. French

As you can imagine, most of the war on this front was between the cities of Changsha and Wuhan. The first major full French (to be used for the Central Theatre instead of the Northern Theatre) and British reinforcement-armies arrived in spring of 1852, where they were immediately sent to fight along the Changsha-Wuhan front. The Changsha-Wuhan front went quickly into a deadlock, and would stay like this for years. In 1853, another French contingent arrived in Shanghai, and was determined to march south to capture Hong Kong and Canton and secure every port on the way.

Sadly for the French, another contingent of British arrived in Canton not long later, and was given the same orders. They met near Quanzhou. A hard battle was fought, but the Brits secured victory when another battalion moved in from the Changsha-Wuhan front and secured the victory at Quanzhou. The British army marched north before being stopped at Fuzhou not to far away.

For the next 3 years the fronts had stalled at Changsha and Fuzhou, before finally in 1856, a breakthrough happened for the British as Qing manpower was finally depleting, either running to the enemy or just simply abandoning their post. Wuhan would finally fall in August of 1856, and is seen as the end of the the Central Theatre and the traditional war.

Northern theatre: Russians vs. French

The first French reinforcement to arrive in China came in early 1852, where they went to try to relieve Beijing. In the Relief of Beijing, French troops were able to open a passage, but only long enough to save the Imperial family, after which the opening broke and Beijing would fall in March. The Royal family would be sent to Nanjing to witness their empire collapse around them.

Unlike the Central theatre, the Northern theatre was vast and mobile, stretching from the Tibetan border to the Yellow Sea. Xi’an and Weifang were both major centers of battle, each falling at least three times to the opposing side. Nanjing itself was under threat two separate times.

The war finally swept into Russian once and for all in 1856 at yet another battle of Xi’an, where Chinese manpower finally ran to low and in September 1856, a month after the fall of Wuhan, Nanjing would fall and the Qing emperor would go into exile in Paris.

The Marauders’ war: The Qing-French resistance

In August 1856, the French armies were getting onto their boats in Shanghai to leave for back home. One army group, under the leadership of General Philippe Sainte-Marie, decided to stay behind however, to fight a guerrilla war. Sainte-Marie and a thousand men, 900 of which were part of the Qing family or the most loyal Qing soldiers, snuck out of the front near Nanjing and made their first attack not to far away. Another 2 years of a lesser war had begun.

The first couple months was made up of heading north on the Yellow toward Beijing, raiding Russo-Taiping army camps and generally pro-Taiping villages. Sainte-Marie’s army always made sure to stay just out of reach of the opposing armies, and couldn’t be caught, no matter how much Russian armies chased them. Sainte-Marie’s army finally disappeared in December of 1856 in Beijing, where they stayed for the winter, blending into the city. Many of civilians in Beijing who were still loyal to the Qing decided to join the cause, and in March of the following year, Sainte-Marie’s army left Beijing, left it by burning it to the ground. With Sainte-Marie’s army grown to 10,000 and committing such a crime as burning Beijing to the ground, the Taiping, Russians, and Brits were to make sure that Sainte-Marie’s army would be stopped. Even Napoleon II, when hearing of what Sainte-Marie did, declared that he and all the Qing family that joined him were no longer welcome in France (unless they won).

After burning Beijing, Sainte-Marie’s army (commonly referred to as the Marauder’s Army, Philippe Sainte-Marie himself gaining the title as “Philippe the Marauder”) headed south to the Yellow River to go up and down that hitting Xi’an, Ordos, Wuhai, then took a shortcut back to raid Xi’an again and heading south to raid the Yangtze. The Marauder’s Army raided Chongqing, and was heading to attack Wuhan, but upon hearing that the Taiping Imperial Army was there waiting for him, the Marauder’s Army turned sharply south to Changsha (how fitting). Again, burning Changsha to the ground, the army headed further south before disappearing somewhere near Canton/Guangzhou in December. The Taiping Imperial Army searched frantically for the Marauder in Guangzhou, but he couldn’t be found anywhere. It sure didn’t help that he was actually hiding in Nanning two hundred kilometers west, but the Taipings wouldn’t figure that out until Nanning was also burned to the ground the following spring, and the Marauders went on another campaign.

Philippe Sainte-Marie thought of a clever plan that instead of heading further west to run away from the Taiping Imperial Army, he was just sneak around it by heading south, attack Zhanjiang and then go on to Guangzhou. This proved to be a mistake, for as soon as the Taiping Imperial Army heard of the attack on Zhanjiang, they would only be about a 6 hour’s travel behind them. There was no attempting to hide, for if they hid they would be found. If they stayed to for too long in a city the TIA would catch them, they could barely actually raid anymore. They had to spend an extra hour each day travelling just to get extra distance on the TIA, but in June they were finally caught in the city they started in, Shanghai. All the Marauder’s were either killed in the skirmish at Shanghai or executed not long later. Philippe the Marauder himself would get special treatment… A lifetime in the Taiping Oubliette.

American Civil War 1861-1865

Since the loss of the Great Gamble, France had been working hard to make sure the United States of America becomes a definitive ally of France instead of a neutral power that generally agrees with them. Britain had been doing the same, trying to ride the momentum of the Great Gamble to make sure America becomes their ally. As such, the two were constantly trying to meddle in American politics, and, oh, it appears America was dividing itself based on their thoughts of Slavery, what a perfect opportunity. Those opposing slavery ended up aligning with France, with those favoring slavery aligned with Britain. French diplomats would go on and on about how evil slavery is, while Britain would say that although they don’t allow slavery, they’re okay with others doing so.

The French and Brits would purposefully try to start conflict, pointing fingers at opposing diplomats and their allies. Personal attacks, like that of Preston Brooks against Charles Sumner, Henry S. Foote and Thomas Benton against each other, and even those on the same side battled each other in a argument over how extreme their sides should become.

The argument eventually came to a head in 1860, when Pro-British, Pro-Slaverly men stormed voting polls across the country, even invading nearby non-slave states, to make sure their candidate, Moise Severin, gets power. While legally, it worked, Moise Severin and his running mate would be assassinated by Pro-French Americans before he get the presidency, leaving the President Pro Tempore of the US Senate - Kenneth Victors, who was Pro-French (but oddly neutral to slavery) - as President to be. The South, understandably, didn’t like this. The North (while celebrating the death of Moise Severin) said that the law is the law and thus that Kenneth Victors should be president, not to mention that the only reason Severin won the election anyways was because of vote-rigging. By the time that Kenneth Victors would ascend to the presidency, blood was already flowing in the streets, and the South gathered an army of Pro-Slavers to march on Washington and get a different president in, while what remained of the true US army gathers to defend Kenneth Victors.

French and British troops were suddenly flowing into the United States to support their respective sides (interestingly, New York was the main staple port for the French and Pro-French America, New Orleans was the staple port for the British and Pro-British America). The first battle was the battle of Alexandria, just south of Washington and the flash of cannons could be seen easily from Washington. This battle contained no French or British troops, though. Instead, the first battle that would contain French and/or British troops would be the battle of New Orleans (1861), in which French sailors flying under the United States banner tried and failed to capture New Orleans, being pushed off by British ships.

There were two main fronts in the American Civil War: The Virginia Front, and the Mississippi front. The American troops mostly focused on the Virginia Front, while they sent the Europeans to the Mississippi front. Now that isn’t to say that Europeans didn’t serve in Virginia (mostly Officers), nor Americans in Mississippi (they still made up a large percentage of the army, though certainly not the majority).

Virginia Front and the Atlantic

The Southern insurgents started off very disorganized, a stark difference to the American Government army, headed by general Robert Scotts. The Southern insurgency can be mostly described as a coalition of self-declared generals and their self-described armies running around trying to beat the government. Not only this, but the North also had an industrial advantage and a discipline advantage (getting most of the army, while only a few defectors joined the Southern Insurgency). The insurgency should have been over by Christmas.

That was before the European Intervention. By June, British officers (most important of which was Alexander Palmer) came and replaced the Southern Insurgent Generals, disciplining them in the same way that Baron von Steuben disciplined the American Revolutionaries almost a century before. The first signs of slowing came in August, right after Richmond was reclaimed, and by Christmas the Virginia Front had almost came to complete halt at the Virginia-North Carolina border and Norfolk.

Britain used her superior navy to try to block out the 3 most important bays in America: Chesapeake, Delaware, and New York bays. While Chesapeake and Delaware were mostly successful, the New York bay blockade was not, as the Brits were unable to block both New York bay and her sister Long Island sound, meaning the whole blockade of New York was for all intents and purposes a failure. But for the blockades that did work, it meant that Washington, Baltimore, Northern-controlled Richmond, and Philadelphia were all blocked out by sea, making the French trek to the front needlessly longer. Not that it really mattered, French and British ships flying French and British flags were almost never attacked out of fear of launching a larger war.

Norfolk sat as a major fortress for a year, Robert Scotts demanding its surrender and Alexander Palmer carefully keeping the defenses up. Two new pieces of weaponry were introduced almost specifically for this siege: the French Flying Shell (a new advanced Howitzer that used relatively advanced indirect fire techniques) and the British Repeating Rifle (Gatling Gun). The Repeating Rifle made assaults on the town costly affairs, while the Flying Shell made it unnecessary to do so. While the siege of Norfolk went on, other parts of the Northern Army marched through North Carolina, capturing Raleigh and Greensboro.

Eventually, the storehouses and supplies at Norfolk became too diminished for Palmer’s liking, and so throughout November, he had part of his garrison army slip out of Norfolk with orders to go to Elizabeth City, North Carolina, just 40 km south. By the end of November, Palmer had escaped Norfolk without Scotts ever being the wiser, and was Scotts ever made the fool when he found out halfway through December that he was bombarding an empty city as his enemy was reinforcing down south. Scotts was sacked for his mistake and moved to the Mississippi front, which was at the time a losing front. He was replaced with Richard P. Geiger.

Geiger believed that Palmer could safely be ignored, and instead of marching his armies to Elizabeth City, he rather decided to turn his men to Raleigh and, more importantly, Charlotte, and try to capture the major population centers throughout the South, leaving Norfolk in January. Now it was time for Palmer to look like the fool as his plan to deteriorate the US government army through only defensive battles would have to be set aside and he made chase with Geiger. Geiger knew that Palmer would chase him all over the front, and so Geiger could place himself anywhere he wished and give himself a week to prepare for a battle. Instead of going to Charlotte, like he intended, he instead fled into the mountains of western North Carolina, quickly capturing Asheville and the surrounding hills, preparing for a grand defense.

The battle of Pisgah was a tremendous success for Geiger and Palmer fled to Charlotte and prepared his own defence. At Charlotte, he wrote to the government of Britain, saying he believed the cause was lost in America, despite Britain’s surprising success on the Mississippi river. Palmer was forced to defend Charlotte from Geiger’s forces and contemporaries in the battles of Belmont, Lake Norman, and Concord. While all narrow victories for Palmer, he was trapped in Charlotte, and forced to push out of the suffocating Charlotte, breaking out and setting up a position to the south at Rock Hill, although that September he was forced to flee from there as well. As fled, the last of North Carolina fell back to the American Government

Palmer sat in Columbia, South Carolina for the winter, with Geiger in Charlotte, North Carolina. Palmer was told that he had one year to turn the war around, or he’d be replaced just as his former nemesis Scotts was. Palmer decided that Columbia needed to become a fortress, so throughout the winter months, Palmer had his army and any volunteers available to make a wall around Columbia, and then another two layers of walls inside, including one of them on an island in the middle of the Congaree river. The fortifications were shifty, but they were better than nothing. The walls were lined with the repeating rifles and standard cannons, and Palmer was ready to fight.

And fight they did, for when Spring came, Geiger came down onto Columbia and was shocked as to what he saw. He bunkered in for a long and seemingly never ending siege. Geiger pushed to take the walls time and time again, only to be mowed down by the repeating rifles, and it seemed that the flying shell was doing minimal damage to the defenders. This was the first battle in the Virginia front for a long time that saw many more Government casualties than Insurgent, and Columbia soon became a symbol of the Southern Insurgency.

Sadly, for the insurgency, that didn’t stop Charleston from being captured, cutting off the Congaree river. The sudden knowledge of the Surprise war and its loss was devastating for British moral, and the loss of British moral affected the insurgents as well. Throughout the summer and fall, Geiger would continue his siege, and more and more insurgents deserted to Geiger. Meanwhile, other cities across South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida fell as well, with British generals deciding to head back home and their armies collapsed from loss of moral. Palmer was the last one in Virginia, and he no longer wanted to be there. On November 3rd, 1864, Palmer surrendered to Geiger under the condition that he could live in America (so that he wouldn’t suffer humiliation at home).

The next week, the first election since the insurgency began were held, with elections taking place in Virginia and North Carolina. Incumbent President Kenneth Victors won in a wild landslide, repeating the phrase “Victors for Victory!”

Mississippi Front and the Gulf

The war in Mississippi started off with a slight French advantage on land and a major British advantage at sea. With the front starting off at the 36th Parallel North, the French army was prepared to march on Memphis. Sadly for the French, they would be stopped just north at Memphis, and the French and Brits were preparing for a repeat of what happened at Changsha and Wuhan, with the French and British armies marching between Saint Louis and Memphis.

Fortunately for the British, it didn’t end up this was, for in the next year, the 1st Explorer’s War in the Congo (or Surprise War) would begin, and French troops and supply would diverted from America to the Congo, with Britain scratching their heads why. Most figured that France was probably preparing for a war elsewhere, or had given up on the American war (hardly a chance). But, nonetheless with the French force limited on the Mississippi Front, Britain gained the upper edge and started the march up the Mississippi River, capturing Saint Louis by Christmas of 1862, and had begun a siege of Chicago the following year.

The Northern Americans fought hard to try to break the siege, cut off British supply lines, or just to negotiate as good of a peace as they still could (thankfully, the Virginia front was still going decently, with large leaps in progress coming in 1863). Chicago did eventually fall in early 1864, which the Brits believed would be the end of the Mississippi front, despite some resistance volunteers coming in from Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota. The Brits were wrong to assume.

With the discovery of the Surprise War and France’s victory in it before it even started, many Brits suddenly had a drop in morale, but not enough to take them out of the war. Britain still held Chicago and the entirety of the Mississippi River up to Saint Louis (as far as they really needed to go), and from there, up the Illinois river to Chicago, dividing the United States. But, they would be facing off against a new surge of French Troops, arriving back from the Congo, led by Vincent Durant (Jean-Marie ‘Le Toulonnais’ was out on another mission in the Sahara). But also arriving from the Congo was Joseph Crawford, hoping to regain some of his lost honor.

Durant’s first strike was against Saint Louis, quickly capturing it while the British were still in Chicago. The British armies led by Crawford marched quickly on to Saint Louis and put it under siege. Durant seeked to pull the same trick that Le Toulonnais had pulled on Crawford back at Fort Durant, tricking Crawford into a peace behind French lines so he could be captured, but this time Crawford knew it was a trap, and while Durant stood waiting for his adversary, one of Crawford’s men shot Durant. While he survived, he wouldn’t be able to effectively lead his armies. Crawford was able to regain Saint Louis under the conditions that Durant would get safe passage to New York City so he could more effectively recover, the remaining French forces would surrender all arms, and that said force would get a 2 day’s head start to run to a more effective place to defend and get weapons again.

British forces lined the Mississippi by the time the Virginia front finally ended. The rebellion in the East had finally been put down, and it was time to put down the rebellion in the West. Richard Geiger was put in charge on the Southwest (Louisiana), former general of Virginia Robert Soctts was put in charge of the Northwest (Illinois), and a replacement general for Durant, Philippe Berger, led the center (Missouri).

Crawford, put at the helm of the entire West, stood no chance, and he wished that all British troops in America leave. They had already lost the important front, that in Virginia, any victory in the Mississippi would be minimal, even if Britain could establish a completely separate state west of the Mississippi, the population would be nearly nonexistent and there seems to be no resources in the area.

The British government agreed, but refused a flat-out surrender. Instead, they wanted their troops to return to Britain or Canada before they’ll negotiate (since they technically never declared war, they hoped that a few hundred thousand pounds would work). Thus began the great retreat, in which British soldiers north of Saint Louis would sweep north-west back into Canada (and try to burn Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota on the way), while soldiers south of Saint Louis would collapse the line to the Texan coast, where they’d get on British ship and go on their merry way.

The Northern retreat went as expected, as Robert Scotts chased them from Illinois, but witnessed the destruction of the Upper Mississippi along with the way. The two most infamous incidents were when the entirety of Chicago was burned to the ground, and when British troops in Minneapolis burned the mills, and a good amount of the rest of the city with it. The Southern retreat didn’t go quite as expected, mostly thanks to one major flaw that Crawford couldn’t imagine; an evolved, advanced, and much larger form of cavalry warfare, a much more mobile warfare, where the French General Philippe Berger was able to get around the retreating and harass the northern end of the British armies from the front and rear, and ‘chewed’ down from there. Most of the British army survived, but only by moving in a way Crawford hadn’t intended, clumping together into a giant mass. The British army gathered in Friendship, Texas, where they were to hold out while the French and Americans assaulted the town

In April 1865, the British fleet finally arrived, and the last of the British troops fled America, the de facto end of the American Civil War.

Since the loss of the Great Gamble, France had been working hard to make sure the United States of America becomes a definitive ally of France instead of a neutral power that generally agrees with them. Britain had been doing the same, trying to ride the momentum of the Great Gamble to make sure America becomes their ally. As such, the two were constantly trying to meddle in American politics, and, oh, it appears America was dividing itself based on their thoughts of Slavery, what a perfect opportunity. Those opposing slavery ended up aligning with France, with those favoring slavery aligned with Britain. French diplomats would go on and on about how evil slavery is, while Britain would say that although they don’t allow slavery, they’re okay with others doing so.

The French and Brits would purposefully try to start conflict, pointing fingers at opposing diplomats and their allies. Personal attacks, like that of Preston Brooks against Charles Sumner, Henry S. Foote and Thomas Benton against each other, and even those on the same side battled each other in a argument over how extreme their sides should become.

The argument eventually came to a head in 1860, when Pro-British, Pro-Slaverly men stormed voting polls across the country, even invading nearby non-slave states, to make sure their candidate, Moise Severin, gets power. While legally, it worked, Moise Severin and his running mate would be assassinated by Pro-French Americans before he get the presidency, leaving the President Pro Tempore of the US Senate - Kenneth Victors, who was Pro-French (but oddly neutral to slavery) - as President to be. The South, understandably, didn’t like this. The North (while celebrating the death of Moise Severin) said that the law is the law and thus that Kenneth Victors should be president, not to mention that the only reason Severin won the election anyways was because of vote-rigging. By the time that Kenneth Victors would ascend to the presidency, blood was already flowing in the streets, and the South gathered an army of Pro-Slavers to march on Washington and get a different president in, while what remained of the true US army gathers to defend Kenneth Victors.

French and British troops were suddenly flowing into the United States to support their respective sides (interestingly, New York was the main staple port for the French and Pro-French America, New Orleans was the staple port for the British and Pro-British America). The first battle was the battle of Alexandria, just south of Washington and the flash of cannons could be seen easily from Washington. This battle contained no French or British troops, though. Instead, the first battle that would contain French and/or British troops would be the battle of New Orleans (1861), in which French sailors flying under the United States banner tried and failed to capture New Orleans, being pushed off by British ships.

There were two main fronts in the American Civil War: The Virginia Front, and the Mississippi front. The American troops mostly focused on the Virginia Front, while they sent the Europeans to the Mississippi front. Now that isn’t to say that Europeans didn’t serve in Virginia (mostly Officers), nor Americans in Mississippi (they still made up a large percentage of the army, though certainly not the majority).

Virginia Front and the Atlantic

The Southern insurgents started off very disorganized, a stark difference to the American Government army, headed by general Robert Scotts. The Southern insurgency can be mostly described as a coalition of self-declared generals and their self-described armies running around trying to beat the government. Not only this, but the North also had an industrial advantage and a discipline advantage (getting most of the army, while only a few defectors joined the Southern Insurgency). The insurgency should have been over by Christmas.

That was before the European Intervention. By June, British officers (most important of which was Alexander Palmer) came and replaced the Southern Insurgent Generals, disciplining them in the same way that Baron von Steuben disciplined the American Revolutionaries almost a century before. The first signs of slowing came in August, right after Richmond was reclaimed, and by Christmas the Virginia Front had almost came to complete halt at the Virginia-North Carolina border and Norfolk.

Britain used her superior navy to try to block out the 3 most important bays in America: Chesapeake, Delaware, and New York bays. While Chesapeake and Delaware were mostly successful, the New York bay blockade was not, as the Brits were unable to block both New York bay and her sister Long Island sound, meaning the whole blockade of New York was for all intents and purposes a failure. But for the blockades that did work, it meant that Washington, Baltimore, Northern-controlled Richmond, and Philadelphia were all blocked out by sea, making the French trek to the front needlessly longer. Not that it really mattered, French and British ships flying French and British flags were almost never attacked out of fear of launching a larger war.

Norfolk sat as a major fortress for a year, Robert Scotts demanding its surrender and Alexander Palmer carefully keeping the defenses up. Two new pieces of weaponry were introduced almost specifically for this siege: the French Flying Shell (a new advanced Howitzer that used relatively advanced indirect fire techniques) and the British Repeating Rifle (Gatling Gun). The Repeating Rifle made assaults on the town costly affairs, while the Flying Shell made it unnecessary to do so. While the siege of Norfolk went on, other parts of the Northern Army marched through North Carolina, capturing Raleigh and Greensboro.

Eventually, the storehouses and supplies at Norfolk became too diminished for Palmer’s liking, and so throughout November, he had part of his garrison army slip out of Norfolk with orders to go to Elizabeth City, North Carolina, just 40 km south. By the end of November, Palmer had escaped Norfolk without Scotts ever being the wiser, and was Scotts ever made the fool when he found out halfway through December that he was bombarding an empty city as his enemy was reinforcing down south. Scotts was sacked for his mistake and moved to the Mississippi front, which was at the time a losing front. He was replaced with Richard P. Geiger.

Geiger believed that Palmer could safely be ignored, and instead of marching his armies to Elizabeth City, he rather decided to turn his men to Raleigh and, more importantly, Charlotte, and try to capture the major population centers throughout the South, leaving Norfolk in January. Now it was time for Palmer to look like the fool as his plan to deteriorate the US government army through only defensive battles would have to be set aside and he made chase with Geiger. Geiger knew that Palmer would chase him all over the front, and so Geiger could place himself anywhere he wished and give himself a week to prepare for a battle. Instead of going to Charlotte, like he intended, he instead fled into the mountains of western North Carolina, quickly capturing Asheville and the surrounding hills, preparing for a grand defense.

The battle of Pisgah was a tremendous success for Geiger and Palmer fled to Charlotte and prepared his own defence. At Charlotte, he wrote to the government of Britain, saying he believed the cause was lost in America, despite Britain’s surprising success on the Mississippi river. Palmer was forced to defend Charlotte from Geiger’s forces and contemporaries in the battles of Belmont, Lake Norman, and Concord. While all narrow victories for Palmer, he was trapped in Charlotte, and forced to push out of the suffocating Charlotte, breaking out and setting up a position to the south at Rock Hill, although that September he was forced to flee from there as well. As fled, the last of North Carolina fell back to the American Government

Palmer sat in Columbia, South Carolina for the winter, with Geiger in Charlotte, North Carolina. Palmer was told that he had one year to turn the war around, or he’d be replaced just as his former nemesis Scotts was. Palmer decided that Columbia needed to become a fortress, so throughout the winter months, Palmer had his army and any volunteers available to make a wall around Columbia, and then another two layers of walls inside, including one of them on an island in the middle of the Congaree river. The fortifications were shifty, but they were better than nothing. The walls were lined with the repeating rifles and standard cannons, and Palmer was ready to fight.

And fight they did, for when Spring came, Geiger came down onto Columbia and was shocked as to what he saw. He bunkered in for a long and seemingly never ending siege. Geiger pushed to take the walls time and time again, only to be mowed down by the repeating rifles, and it seemed that the flying shell was doing minimal damage to the defenders. This was the first battle in the Virginia front for a long time that saw many more Government casualties than Insurgent, and Columbia soon became a symbol of the Southern Insurgency.

Sadly, for the insurgency, that didn’t stop Charleston from being captured, cutting off the Congaree river. The sudden knowledge of the Surprise war and its loss was devastating for British moral, and the loss of British moral affected the insurgents as well. Throughout the summer and fall, Geiger would continue his siege, and more and more insurgents deserted to Geiger. Meanwhile, other cities across South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida fell as well, with British generals deciding to head back home and their armies collapsed from loss of moral. Palmer was the last one in Virginia, and he no longer wanted to be there. On November 3rd, 1864, Palmer surrendered to Geiger under the condition that he could live in America (so that he wouldn’t suffer humiliation at home).

The next week, the first election since the insurgency began were held, with elections taking place in Virginia and North Carolina. Incumbent President Kenneth Victors won in a wild landslide, repeating the phrase “Victors for Victory!”

Mississippi Front and the Gulf

The war in Mississippi started off with a slight French advantage on land and a major British advantage at sea. With the front starting off at the 36th Parallel North, the French army was prepared to march on Memphis. Sadly for the French, they would be stopped just north at Memphis, and the French and Brits were preparing for a repeat of what happened at Changsha and Wuhan, with the French and British armies marching between Saint Louis and Memphis.

Fortunately for the British, it didn’t end up this was, for in the next year, the 1st Explorer’s War in the Congo (or Surprise War) would begin, and French troops and supply would diverted from America to the Congo, with Britain scratching their heads why. Most figured that France was probably preparing for a war elsewhere, or had given up on the American war (hardly a chance). But, nonetheless with the French force limited on the Mississippi Front, Britain gained the upper edge and started the march up the Mississippi River, capturing Saint Louis by Christmas of 1862, and had begun a siege of Chicago the following year.

The Northern Americans fought hard to try to break the siege, cut off British supply lines, or just to negotiate as good of a peace as they still could (thankfully, the Virginia front was still going decently, with large leaps in progress coming in 1863). Chicago did eventually fall in early 1864, which the Brits believed would be the end of the Mississippi front, despite some resistance volunteers coming in from Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota. The Brits were wrong to assume.

With the discovery of the Surprise War and France’s victory in it before it even started, many Brits suddenly had a drop in morale, but not enough to take them out of the war. Britain still held Chicago and the entirety of the Mississippi River up to Saint Louis (as far as they really needed to go), and from there, up the Illinois river to Chicago, dividing the United States. But, they would be facing off against a new surge of French Troops, arriving back from the Congo, led by Vincent Durant (Jean-Marie ‘Le Toulonnais’ was out on another mission in the Sahara). But also arriving from the Congo was Joseph Crawford, hoping to regain some of his lost honor.

Durant’s first strike was against Saint Louis, quickly capturing it while the British were still in Chicago. The British armies led by Crawford marched quickly on to Saint Louis and put it under siege. Durant seeked to pull the same trick that Le Toulonnais had pulled on Crawford back at Fort Durant, tricking Crawford into a peace behind French lines so he could be captured, but this time Crawford knew it was a trap, and while Durant stood waiting for his adversary, one of Crawford’s men shot Durant. While he survived, he wouldn’t be able to effectively lead his armies. Crawford was able to regain Saint Louis under the conditions that Durant would get safe passage to New York City so he could more effectively recover, the remaining French forces would surrender all arms, and that said force would get a 2 day’s head start to run to a more effective place to defend and get weapons again.

British forces lined the Mississippi by the time the Virginia front finally ended. The rebellion in the East had finally been put down, and it was time to put down the rebellion in the West. Richard Geiger was put in charge on the Southwest (Louisiana), former general of Virginia Robert Soctts was put in charge of the Northwest (Illinois), and a replacement general for Durant, Philippe Berger, led the center (Missouri).

Crawford, put at the helm of the entire West, stood no chance, and he wished that all British troops in America leave. They had already lost the important front, that in Virginia, any victory in the Mississippi would be minimal, even if Britain could establish a completely separate state west of the Mississippi, the population would be nearly nonexistent and there seems to be no resources in the area.

The British government agreed, but refused a flat-out surrender. Instead, they wanted their troops to return to Britain or Canada before they’ll negotiate (since they technically never declared war, they hoped that a few hundred thousand pounds would work). Thus began the great retreat, in which British soldiers north of Saint Louis would sweep north-west back into Canada (and try to burn Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota on the way), while soldiers south of Saint Louis would collapse the line to the Texan coast, where they’d get on British ship and go on their merry way.

The Northern retreat went as expected, as Robert Scotts chased them from Illinois, but witnessed the destruction of the Upper Mississippi along with the way. The two most infamous incidents were when the entirety of Chicago was burned to the ground, and when British troops in Minneapolis burned the mills, and a good amount of the rest of the city with it. The Southern retreat didn’t go quite as expected, mostly thanks to one major flaw that Crawford couldn’t imagine; an evolved, advanced, and much larger form of cavalry warfare, a much more mobile warfare, where the French General Philippe Berger was able to get around the retreating and harass the northern end of the British armies from the front and rear, and ‘chewed’ down from there. Most of the British army survived, but only by moving in a way Crawford hadn’t intended, clumping together into a giant mass. The British army gathered in Friendship, Texas, where they were to hold out while the French and Americans assaulted the town

In April 1865, the British fleet finally arrived, and the last of the British troops fled America, the de facto end of the American Civil War.

1st Explorers' War-Congo War 1862-1864

Since the Treaty of Amsterdam, Africa remained the most contested continent between the French and the British, especially due to the vast, unclaimed and unexplored land that both sides desired if only to keep it from the other. And do to limits in technology and the stubbornness of the locals, this was how it was suppose to remain, at least for a while.

The first step to ending this status quo came, in hindsight, in 1844, when developments in medicine made it so that European men could enter Central Africa without being completely wiped out from disease. The Second development came in 1862, when the long reigning king of the Kongo finally died. He refused access to British ships to allow them to venture up the Congo, despite him being officially part of the Anglo-Sphere. When he finally died, his heir came to power and agreed to sell a part of their land north of the Congo River, giving the river access to British Ships. Britain immediately started to organize an expedition to explore the Upper Congo, led by General Joseph Crawford.

When Napoleon II of France heard that the Kingdom of the Kongo sold that land to the Brits, he immediately knew what was going on and organized an expedition of his own led by General Vincent “Le Malouin" Durant. They hoped that do to the fact that the Mouth of the Congo was shared between two states, that France could get away with calling it International Territory (an excuse that Britain would never accept, but maybe the Kongolese could)

Crawford and Durant left from their respective ports at approximately the same time (Crawford from Lisbon, Durant from Barcelona). Their fleets met off the Coast of Guinea, and they tensely followed each other for a day until Crawford’s finally broke off to port in the Gold Coast. Durant’s fleet continued on to a small port on the island of Corisco.

The two would take off once again and meet at the Mouth of the Congo. The two then realized what their adversary's mission was in direct conflict of their own. They started firing upon each other, but Britain won the day and Durant fled south. Little did Crawford know that this victory would indirectly lead to disaster of the British Expedition.

While Crawford started building a fort on the Mouth of the Congo (he named the fort as “Fort Anne,” after the current Queen Anne II), Durant fled south and landed on the Kongolese coast, where he founded a small supply port so that his ships could be fixed, and once fixed they could establish a supply line with Durant. Durant led his army through the Kongo and overthrew the new Kongolese King, replacing him with pro-French King.

Crawford sailed up the Congo River while Fort Anne was being finished, and Durant’s army made it to the Inner Congo River with Crawford’s fleet not to far ahead. Durant’s army mostly had to get around on foot, which certainly made it much more difficult. Throughout their trek along the Congo River, Durant’s Army consistently removed any British Flags that hung from trees or primitive flag poles, marking Crawford’s British claims. Finally, at the confluence of the Congo and Kasai Rivers, Durant founded a fort known as “Fort Durant” (after himself), although the fort had been more popularly been called “La Forte Fort (Fort Strong/ Strong Fort).”

Durant had found that British Force had continued up the Middle Congo River, and so decided that Durant would lead his force up the Kasai River, leaving behind a small garrison at Fort Durant led by then unknown Major Jean-Marie “Le Toulonnais” Lachance.

Far from Fort Durant, on the Upper Congo and Lomani Rivers, two separate French Exploration/ Scouting parties discovered similarly sized British forces, who were unaware that the French had returned to the Congo River after the Battle of the Mouth of the Congo. The French attacked the Brits off guard and the British fled. At the same time, a British ship was heading back to Fort Anne to bring supplies back to General Crawford, only to be surprised by the Fort Durant Garrison. They tried to get by, but the ship was heavily damaged, and so headed back upstream to General Crawford. When Crawford heard that French were in the Congo, he panicked and headed downstream with his full force to besiege Fort Durant. Similarly, when General Durant heard of the skirmish between French and English scouts, he knew Crawford would be heading back downstream, so marched his men back to Fort Durant. Sadly, the return of General Durant would take quite a while, so it was left to Major Jean-Marie Lachance to save Fort Durant, but he did have a plan up his sleeve...

When General Crawford returned to place Fort Durant under siege, Jean-Marie came out and offered a truce, naming himself as General Durant. Crawford accepted his truce and entered the Fort to speak of the conditions of surrender, but was captured and held hostage by “Le Toulonnais” and his garrison. The British Force kept up the siege for several months, but under very demoralized conditions, and when the relief force led by the actual General Durant came, the Brits fled back up river.

It was at this point that Fort Anne realized that something was amiss, so sent out a small force to investigate the Congo River. They came just in time for the original British Force to return back to Fort Durant, and the combination of the armies besiege Fort Durant once more.

General Durant finally came out offering peace: The Brits and French would divide the Congo among themselves, each side get the areas they explored (Kasai Basin and Southern Kongo Kingdom to France, Middle Congo Basin and Northern Kongo Kingdom to Britain).

Major Jean-Marie “Le Toulonnais” would be declared the Hero of the Congo and was promoted to Colonel. Vincent Durant would also be praised, but not to the extent of Le Toulonnais. General Crawford would be shunned by the British Military and was almost forced to retire. France was the one got away with the most in this war, with the areas they gained having the majority of Congolese Rubber and Ivory.

In Britain, the war is often called the ‘Surprise War,’ due to the fact that nobody knew that the war was going on until after the conflict was over, due to information not being able to escape the Congo region

Since the Treaty of Amsterdam, Africa remained the most contested continent between the French and the British, especially due to the vast, unclaimed and unexplored land that both sides desired if only to keep it from the other. And do to limits in technology and the stubbornness of the locals, this was how it was suppose to remain, at least for a while.

The first step to ending this status quo came, in hindsight, in 1844, when developments in medicine made it so that European men could enter Central Africa without being completely wiped out from disease. The Second development came in 1862, when the long reigning king of the Kongo finally died. He refused access to British ships to allow them to venture up the Congo, despite him being officially part of the Anglo-Sphere. When he finally died, his heir came to power and agreed to sell a part of their land north of the Congo River, giving the river access to British Ships. Britain immediately started to organize an expedition to explore the Upper Congo, led by General Joseph Crawford.

When Napoleon II of France heard that the Kingdom of the Kongo sold that land to the Brits, he immediately knew what was going on and organized an expedition of his own led by General Vincent “Le Malouin" Durant. They hoped that do to the fact that the Mouth of the Congo was shared between two states, that France could get away with calling it International Territory (an excuse that Britain would never accept, but maybe the Kongolese could)

Crawford and Durant left from their respective ports at approximately the same time (Crawford from Lisbon, Durant from Barcelona). Their fleets met off the Coast of Guinea, and they tensely followed each other for a day until Crawford’s finally broke off to port in the Gold Coast. Durant’s fleet continued on to a small port on the island of Corisco.

The two would take off once again and meet at the Mouth of the Congo. The two then realized what their adversary's mission was in direct conflict of their own. They started firing upon each other, but Britain won the day and Durant fled south. Little did Crawford know that this victory would indirectly lead to disaster of the British Expedition.

While Crawford started building a fort on the Mouth of the Congo (he named the fort as “Fort Anne,” after the current Queen Anne II), Durant fled south and landed on the Kongolese coast, where he founded a small supply port so that his ships could be fixed, and once fixed they could establish a supply line with Durant. Durant led his army through the Kongo and overthrew the new Kongolese King, replacing him with pro-French King.

Crawford sailed up the Congo River while Fort Anne was being finished, and Durant’s army made it to the Inner Congo River with Crawford’s fleet not to far ahead. Durant’s army mostly had to get around on foot, which certainly made it much more difficult. Throughout their trek along the Congo River, Durant’s Army consistently removed any British Flags that hung from trees or primitive flag poles, marking Crawford’s British claims. Finally, at the confluence of the Congo and Kasai Rivers, Durant founded a fort known as “Fort Durant” (after himself), although the fort had been more popularly been called “La Forte Fort (Fort Strong/ Strong Fort).”

Durant had found that British Force had continued up the Middle Congo River, and so decided that Durant would lead his force up the Kasai River, leaving behind a small garrison at Fort Durant led by then unknown Major Jean-Marie “Le Toulonnais” Lachance.

Far from Fort Durant, on the Upper Congo and Lomani Rivers, two separate French Exploration/ Scouting parties discovered similarly sized British forces, who were unaware that the French had returned to the Congo River after the Battle of the Mouth of the Congo. The French attacked the Brits off guard and the British fled. At the same time, a British ship was heading back to Fort Anne to bring supplies back to General Crawford, only to be surprised by the Fort Durant Garrison. They tried to get by, but the ship was heavily damaged, and so headed back upstream to General Crawford. When Crawford heard that French were in the Congo, he panicked and headed downstream with his full force to besiege Fort Durant. Similarly, when General Durant heard of the skirmish between French and English scouts, he knew Crawford would be heading back downstream, so marched his men back to Fort Durant. Sadly, the return of General Durant would take quite a while, so it was left to Major Jean-Marie Lachance to save Fort Durant, but he did have a plan up his sleeve...

When General Crawford returned to place Fort Durant under siege, Jean-Marie came out and offered a truce, naming himself as General Durant. Crawford accepted his truce and entered the Fort to speak of the conditions of surrender, but was captured and held hostage by “Le Toulonnais” and his garrison. The British Force kept up the siege for several months, but under very demoralized conditions, and when the relief force led by the actual General Durant came, the Brits fled back up river.

It was at this point that Fort Anne realized that something was amiss, so sent out a small force to investigate the Congo River. They came just in time for the original British Force to return back to Fort Durant, and the combination of the armies besiege Fort Durant once more.

General Durant finally came out offering peace: The Brits and French would divide the Congo among themselves, each side get the areas they explored (Kasai Basin and Southern Kongo Kingdom to France, Middle Congo Basin and Northern Kongo Kingdom to Britain).

Major Jean-Marie “Le Toulonnais” would be declared the Hero of the Congo and was promoted to Colonel. Vincent Durant would also be praised, but not to the extent of Le Toulonnais. General Crawford would be shunned by the British Military and was almost forced to retire. France was the one got away with the most in this war, with the areas they gained having the majority of Congolese Rubber and Ivory.

In Britain, the war is often called the ‘Surprise War,’ due to the fact that nobody knew that the war was going on until after the conflict was over, due to information not being able to escape the Congo region

2nd Explorers’ War- Berber Wars 1865-1871

Starting almost immediately after the end of the 1st Explorers’ War, Colonel Jean-Marie “Le Toulonnais” was sent on a mission into the Berber lands, Sahara, where he was introduced to a small nomadic tribe of Berbers, led by their King Izem, chosen because Izem’s perceived loyalty and good relations with the French (including being able to speak the language). Jean-Marie was given 5000 men (which was equal in size to the entire Berber tribe) and one instruction: “Make them an empire,” and that he planned to do.

Working alongside King Izem (who also acted as translator), Le Toulonnais was able to annex large swaths of the Western Sahara, either through conquest or, later on, convincing them to subjugate themselves to King Izem. Although the army Le Toulonnais was given was quite small, it was still equal in size to most of the rival Berber tribes, and on top of that he had far superior technology in almost every way, so any 1-on-1 match would be a complete slaughter for the opponents, and the couple times they did come across a larger army, they would be slaughtered as well.

Two years following joining King Izem, this small Berber tribe had united all the independent Berber people, and was able to wield an army of it's own. Le Toulonnais was promoted to General and commander of the newly created Armée des Allies (comparable to our French Foreign Legion), and was given permission by Napoleon II to return home, but Le Toulonnais and King Izem were already plotting to expand the Berber Empire, and with Napoleon’s permission, in November 1867, the Berber Empire declared war upon and invaded Morocco.