Post by flyingsquirrel on Apr 6, 2016 4:44:11 GMT

I've never really done one of these before, so I hope the formatting and general approach work for everyone. This is a scenario that I started developing as a premise for some election scenarios to be used with the 270soft simulators, and I thought it might be fun to get into more detail with some of it. As such, the focus will be mostly on political history and how prominent political leaders fit into a different system and party structure, as opposed to major divergences in terms of events. I've written an intro explaining how this came about and the recent context, but most of it will take the form of transcript excerpts from news reports and debates in Parliament.

SUMMARY

This scenario imagines an alternate history in which the United States achieved independence from the United Kingdom in a more gradual fashion akin to what occurred in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. No Revolutionary War was ever fought, slavery was abolished in accordance with the UK’s Slavery Abolition Act 1833, and there was no Civil War in the 19th century. (However, Southern lawmakers did enact considerable institutionalized discrimination after 1833, similar to what happened after the Civil War in real life, with racism and oppression of African-Americans being a major factor in American politics just as in real life.) The United States was granted full functional independence as the Dominion of United States of America in 1856, an example soon followed by Canada in 1867, and has been referred to only as the United States of America ever since 1904.

The United States has followed the mother country’s example of Westminster-style parliamentary democracy, with a Governor-General serving as nominal head of state but exercising no real powers. Though the Senate exists, most powers rest in the House of Commons (meaning that many real-life Senators are instead incumbents in, or challengers for, seats in the House instead). Seats are informally referred to as “ridings,” and members of the House are referred to as MPs (members of parliament). A nonpartisan electoral commission controls most of the “mechanics” of elections, with the result that partisan gerrymandering and deliberate creation of majority-minority seats largely do not occur, while federal elections are held on national holidays. There is also less expectation that an MP will necessarily live in his or her own riding. Certain social issues such as abortion, same-sex marriage, and capital punishment are typically treated as “conscience votes” in Parliament.

POLITICAL PARTIES

The CONSERVATIVE PARTY has been in power more often than any other party, having emerged from the Tory tradition in the mid-1800s and establishing itself over time as a pro-business, socially traditionalist party that tends to be hawkish on foreign policy, though a more isolationist faction still exists. Economic libertarians have also made the Conservative Party their home, viewing it as an acceptable vehicle for their ideas if sometimes too cautious. A small group of Conservative MPs, however, tend to be more moderate on economic issues and are sometimes referred to as “Red Tories,” though the size and influence of this faction has been shrinking.

The LIBERAL PARTY similarly grew out of the Whig tradition, later becoming home to the Progressive movement of the early 20th century under leaders such as Woodrow Wilson and Robert LaFollette. They are supportive of the welfare state but cautious about government intervention in the economy, while taking left-of-centre positions on social issues most of the time. They lost ground to Labour in the 1930s, receding to third-party status, but rebounded somewhat amidst the anti-government politics of the late ‘70s and ‘80s, during which some moderate voters opposed to the Conservatives turned to them as a more realistic alternative than Labour.

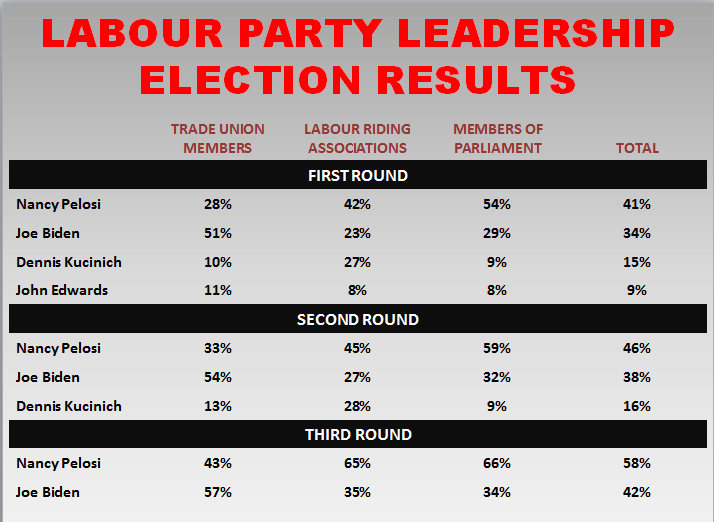

The LABOUR PARTY emerged around the beginning of the 20th century, with roots in the trade union activism of industrial America as well as the populist farmers’ movements in certain rural areas. They take a broadly social democratic approach to the economy and social services, and while a majority of Labour MPs tend to be socially liberal, there is also a sizeable faction of MPs, mostly from the South and Midwest, that take conservative stances on issues such as abortion or same-sex marriage. Labour also have strong historic ties to the African-American community due to their role in getting civil rights legislation passed.

The GREEN PARTY reflects the concerns of the environmental movement and take left-wing stands on most issues, but have thus far been unsuccessful in electing MPs to the House of Commons.

The relationship between Labour and the Liberals is more cooperative than that of, for example, the Liberal-NDP relationship in Canada or the Labour-Liberal Democrat relationship in the United Kingdom. Because the two parties usually need each other’s support to surpass the Conservatives, they encourage local riding associations to negotiate non-competition agreements for certain seats where a split vote would likely lead to a Conservative victory. However, they are not a permanent coalition along the lines of the Australian Liberal-National Coalition. Neither is content simply to be the “junior partner,” both form their own front benches when in opposition, and there are certain ridings where the main competition is between Labour and Liberal candidates with the Conservatives in a distant third place. A number of state parliaments are governed by Labour majorities or Liberal majorities alone, and Liberal-Conservative alliances have even been formed from time to time in certain states.

Correspondence between these parties and their real-life counterparts:

• Labour: Progressive Democrats, economically populist Democrats, other left-wing figures such as Bernie Sanders and Ralph Nader

• Liberal: Fiscally centrist Democrats, liberal Republicans, some moderate Republicans

• Conservative: Conservative Republicans, some moderate Republicans, libertarian conservatives, conservative Democrats

• Green: Mostly overlaps with the real-life Green Party, minus Ralph Nader’s involvement

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Following the election of the Conservative government of Ronald Reagan in 1980, the United States followed the lead of its mother country under Margaret Thatcher, as an increasingly pro-market trend took hold. Taxes were reduced sharply, while Reagan and his allies moved to dismantle or at least shrink the regulatory state. During this period of time, Labour became divided between those who wished to moderate their economic policies and those who remained staunchly opposed to all aspects of the Reagan Government’s agenda; the result was often a watered-down platform that pleased neither side. This proved an opportune situation for the Liberals, who required far less ideological migration to present themselves as the party that would embrace the free market while protecting the foundations of the welfare state, and over several successive elections, the Liberals’ seat total increased just as Labour’s decreased.

Meanwhile, a short-lived populist protest movement led by the billionaire Ross Perot had emerged under the moniker of the Reform Party. Though Perot’s ideology was difficult to pin down and Reform had limited organizational resources, his independent style nevertheless won over many voters, and the result was the fractious “hung parliament” of 1992. Some former Liberal and Conservative voters had defected to Reform, allowing Labour to maintain – just barely – their status as the second-largest party after the Conservatives. With neither the Conservatives nor the old Labour-Liberal alliance able to claim a majority, Perot found himself in the position of kingmaker and flatly demanded that Liberal leader Bill Clinton, the moderate former premier of Arkansas, be appointed Prime Minister over Labour leader Dick Gephardt. Unwilling to return to opposition yet again, Labour reluctantly agreed to a coalition government under Clinton while Reform provided confidence and supply.

The alliance quickly ran into trouble, as Perot’s erratic style proved ill-suited to Parliament and disputes over trade policy left Clinton facing pressure from both Labour and Reform. After a series of Commons defeats on important legislation, Clinton called a snap election in 1993. His gamble paid off, as much of Perot’s support had evaporated over the course of a year, and Perot himself was defeated in his home riding. Most ex-Reform supporters voted Liberal, as did a number of Labour voters who had warmed to Clinton, and for the first time in decades, the Liberals became the largest non-Conservative party in Parliament. The Clinton Government was able to keep Labour on-side for the rest of its time in office, with the 1996 election mostly maintaining the status quo.

The Conservatives had chosen Texas MP and former Premier George W. Bush as their new leader in 1999 after a bruising contest with Arizona MP John McCain. Clinton, after surviving a scandal over an extramarital affair in 1998, decided that he would step aside before the next election, as the Liberals turned to his long-serving Energy Secretary Al Gore to lead them. Many expected Labour to replace Gephardt after the relatively weak showings of the last three elections, but he had since gained what some called “statesman cred” from his performance as Deputy Prime Minister in the coalition government, and he was re-elected as party leader by a comfortable margin.

The election of 2000 saw largely lackluster campaigns from all sides, with Gore struggling to find the balance between touting the positive elements of the Clinton years and trying to present himself as something other than simply the candidate of the status quo, while some former Labour supporters who had supported Clinton in 1993 and 1996 appeared to be “returning home.” Still, Gore might well have won a full term as Prime Minister if not for the outcome in several closely contested ridings in the state of Florida, where disputed counts kept the election result in doubt for over a month before Conservative victories were declared in a series of controversial judicial rulings. Although the combined Liberal-Labour popular vote total surpassed that of the Conservatives, the Conservatives obtained a narrow majority of 221 MPs out of 436.

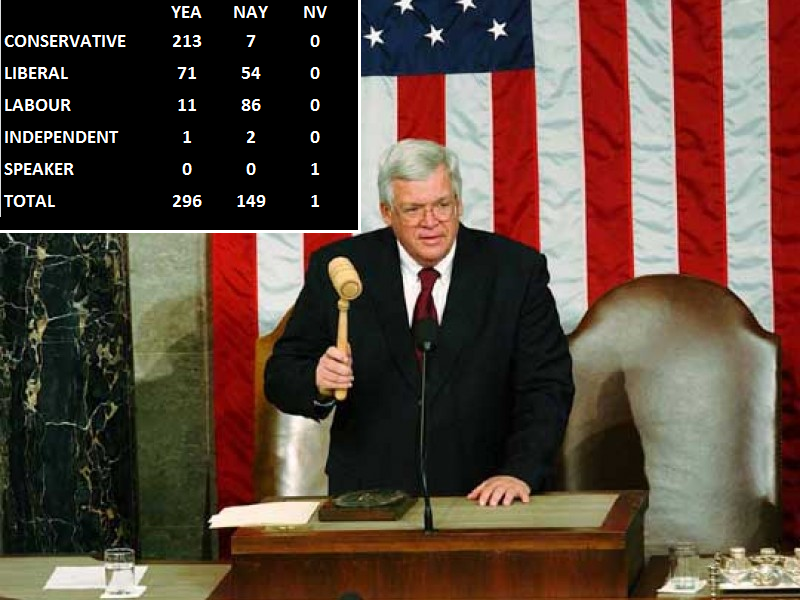

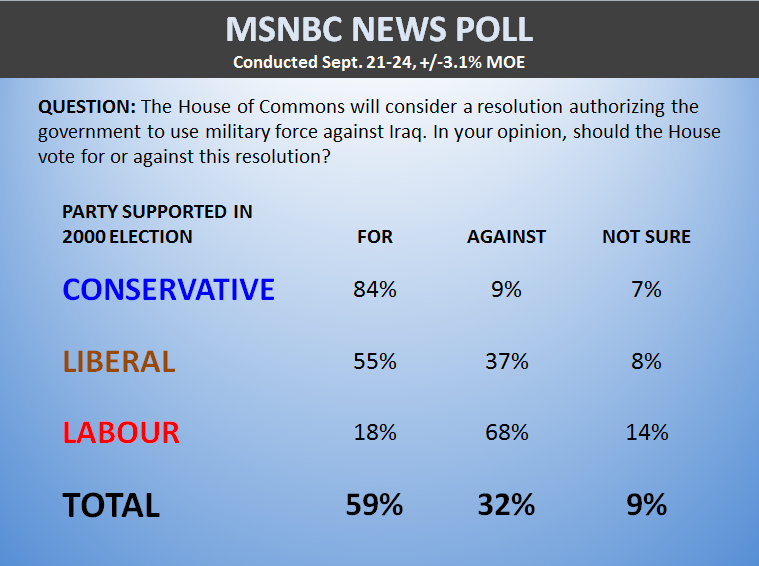

Al Gore resigned as Liberal leader and left parliament shortly after the Bush Government took office, with Massachusetts MP John Kerry elected as the Liberals' new leader. The Bush Government got off to a shaky start, but rose to stratospheric heights of popularity for its decisive response to the terrorist attacks of September 11. Bush’s decision to launch an invasion of Iraq, however, proved more controversial and would come to shape partisan politics over the next several years. It is here that we'll pick up the timeline.

SUMMARY

This scenario imagines an alternate history in which the United States achieved independence from the United Kingdom in a more gradual fashion akin to what occurred in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. No Revolutionary War was ever fought, slavery was abolished in accordance with the UK’s Slavery Abolition Act 1833, and there was no Civil War in the 19th century. (However, Southern lawmakers did enact considerable institutionalized discrimination after 1833, similar to what happened after the Civil War in real life, with racism and oppression of African-Americans being a major factor in American politics just as in real life.) The United States was granted full functional independence as the Dominion of United States of America in 1856, an example soon followed by Canada in 1867, and has been referred to only as the United States of America ever since 1904.

The United States has followed the mother country’s example of Westminster-style parliamentary democracy, with a Governor-General serving as nominal head of state but exercising no real powers. Though the Senate exists, most powers rest in the House of Commons (meaning that many real-life Senators are instead incumbents in, or challengers for, seats in the House instead). Seats are informally referred to as “ridings,” and members of the House are referred to as MPs (members of parliament). A nonpartisan electoral commission controls most of the “mechanics” of elections, with the result that partisan gerrymandering and deliberate creation of majority-minority seats largely do not occur, while federal elections are held on national holidays. There is also less expectation that an MP will necessarily live in his or her own riding. Certain social issues such as abortion, same-sex marriage, and capital punishment are typically treated as “conscience votes” in Parliament.

POLITICAL PARTIES

The CONSERVATIVE PARTY has been in power more often than any other party, having emerged from the Tory tradition in the mid-1800s and establishing itself over time as a pro-business, socially traditionalist party that tends to be hawkish on foreign policy, though a more isolationist faction still exists. Economic libertarians have also made the Conservative Party their home, viewing it as an acceptable vehicle for their ideas if sometimes too cautious. A small group of Conservative MPs, however, tend to be more moderate on economic issues and are sometimes referred to as “Red Tories,” though the size and influence of this faction has been shrinking.

The LIBERAL PARTY similarly grew out of the Whig tradition, later becoming home to the Progressive movement of the early 20th century under leaders such as Woodrow Wilson and Robert LaFollette. They are supportive of the welfare state but cautious about government intervention in the economy, while taking left-of-centre positions on social issues most of the time. They lost ground to Labour in the 1930s, receding to third-party status, but rebounded somewhat amidst the anti-government politics of the late ‘70s and ‘80s, during which some moderate voters opposed to the Conservatives turned to them as a more realistic alternative than Labour.

The LABOUR PARTY emerged around the beginning of the 20th century, with roots in the trade union activism of industrial America as well as the populist farmers’ movements in certain rural areas. They take a broadly social democratic approach to the economy and social services, and while a majority of Labour MPs tend to be socially liberal, there is also a sizeable faction of MPs, mostly from the South and Midwest, that take conservative stances on issues such as abortion or same-sex marriage. Labour also have strong historic ties to the African-American community due to their role in getting civil rights legislation passed.

The GREEN PARTY reflects the concerns of the environmental movement and take left-wing stands on most issues, but have thus far been unsuccessful in electing MPs to the House of Commons.

The relationship between Labour and the Liberals is more cooperative than that of, for example, the Liberal-NDP relationship in Canada or the Labour-Liberal Democrat relationship in the United Kingdom. Because the two parties usually need each other’s support to surpass the Conservatives, they encourage local riding associations to negotiate non-competition agreements for certain seats where a split vote would likely lead to a Conservative victory. However, they are not a permanent coalition along the lines of the Australian Liberal-National Coalition. Neither is content simply to be the “junior partner,” both form their own front benches when in opposition, and there are certain ridings where the main competition is between Labour and Liberal candidates with the Conservatives in a distant third place. A number of state parliaments are governed by Labour majorities or Liberal majorities alone, and Liberal-Conservative alliances have even been formed from time to time in certain states.

Correspondence between these parties and their real-life counterparts:

• Labour: Progressive Democrats, economically populist Democrats, other left-wing figures such as Bernie Sanders and Ralph Nader

• Liberal: Fiscally centrist Democrats, liberal Republicans, some moderate Republicans

• Conservative: Conservative Republicans, some moderate Republicans, libertarian conservatives, conservative Democrats

• Green: Mostly overlaps with the real-life Green Party, minus Ralph Nader’s involvement

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Following the election of the Conservative government of Ronald Reagan in 1980, the United States followed the lead of its mother country under Margaret Thatcher, as an increasingly pro-market trend took hold. Taxes were reduced sharply, while Reagan and his allies moved to dismantle or at least shrink the regulatory state. During this period of time, Labour became divided between those who wished to moderate their economic policies and those who remained staunchly opposed to all aspects of the Reagan Government’s agenda; the result was often a watered-down platform that pleased neither side. This proved an opportune situation for the Liberals, who required far less ideological migration to present themselves as the party that would embrace the free market while protecting the foundations of the welfare state, and over several successive elections, the Liberals’ seat total increased just as Labour’s decreased.

Meanwhile, a short-lived populist protest movement led by the billionaire Ross Perot had emerged under the moniker of the Reform Party. Though Perot’s ideology was difficult to pin down and Reform had limited organizational resources, his independent style nevertheless won over many voters, and the result was the fractious “hung parliament” of 1992. Some former Liberal and Conservative voters had defected to Reform, allowing Labour to maintain – just barely – their status as the second-largest party after the Conservatives. With neither the Conservatives nor the old Labour-Liberal alliance able to claim a majority, Perot found himself in the position of kingmaker and flatly demanded that Liberal leader Bill Clinton, the moderate former premier of Arkansas, be appointed Prime Minister over Labour leader Dick Gephardt. Unwilling to return to opposition yet again, Labour reluctantly agreed to a coalition government under Clinton while Reform provided confidence and supply.

The alliance quickly ran into trouble, as Perot’s erratic style proved ill-suited to Parliament and disputes over trade policy left Clinton facing pressure from both Labour and Reform. After a series of Commons defeats on important legislation, Clinton called a snap election in 1993. His gamble paid off, as much of Perot’s support had evaporated over the course of a year, and Perot himself was defeated in his home riding. Most ex-Reform supporters voted Liberal, as did a number of Labour voters who had warmed to Clinton, and for the first time in decades, the Liberals became the largest non-Conservative party in Parliament. The Clinton Government was able to keep Labour on-side for the rest of its time in office, with the 1996 election mostly maintaining the status quo.

The Conservatives had chosen Texas MP and former Premier George W. Bush as their new leader in 1999 after a bruising contest with Arizona MP John McCain. Clinton, after surviving a scandal over an extramarital affair in 1998, decided that he would step aside before the next election, as the Liberals turned to his long-serving Energy Secretary Al Gore to lead them. Many expected Labour to replace Gephardt after the relatively weak showings of the last three elections, but he had since gained what some called “statesman cred” from his performance as Deputy Prime Minister in the coalition government, and he was re-elected as party leader by a comfortable margin.

The election of 2000 saw largely lackluster campaigns from all sides, with Gore struggling to find the balance between touting the positive elements of the Clinton years and trying to present himself as something other than simply the candidate of the status quo, while some former Labour supporters who had supported Clinton in 1993 and 1996 appeared to be “returning home.” Still, Gore might well have won a full term as Prime Minister if not for the outcome in several closely contested ridings in the state of Florida, where disputed counts kept the election result in doubt for over a month before Conservative victories were declared in a series of controversial judicial rulings. Although the combined Liberal-Labour popular vote total surpassed that of the Conservatives, the Conservatives obtained a narrow majority of 221 MPs out of 436.

Al Gore resigned as Liberal leader and left parliament shortly after the Bush Government took office, with Massachusetts MP John Kerry elected as the Liberals' new leader. The Bush Government got off to a shaky start, but rose to stratospheric heights of popularity for its decisive response to the terrorist attacks of September 11. Bush’s decision to launch an invasion of Iraq, however, proved more controversial and would come to shape partisan politics over the next several years. It is here that we'll pick up the timeline.